Alzheimer’s Disease is a specific condition that, in its most generic form, is referred to as dementia. There are numerous sorts of dementia, but each are characterized by severe impairment of cognitive (or mental) function – including diminishment of memory and reasoning ability – resulting in extreme states of physical and social incapacity. Different dementias may be precipitated by different causes, but Alzheimer’s is basically describable as a degenerative brain disease, usually (but not always) occurring in seniors, in which various protein deposits (called “plaques” or “tangles”) accumulate in, and destroy, brain tissue. And this deterioration occurs progressively, in stages.

But just how many such “stages” does Alzheimer’s have, three or seven Both! Alzheimer’s has three basic stages: (1) early, (2) middle, and (3) late – corresponding to the familiar storytelling categories: beginning, middle, and end. You can get seven stages by making a few additional distinctions. Thus, the expanded list is: (1) no impairment, (2) very mild cognitive impairment, (3) mild cognitive impairment), (4) mild Alzheimer’s, (5) early-moderate stage Alzheimer’s, (6) moderate Alzheimer’s, (7) severe Alzheimer’s.

Some lists talk of three stages, while others speak of seven. Which is it?It is arguable that classifying an Alzheimer’s patient into a particular stage involves a bit of educated guesswork. In broad terms, Alzheimer’s can be thought of as occurring in three stages. But some observers have attempted to carve out finer distinctions, resulting in the creation of several additional stages, yielding seven. (Or…maybe it has five stages! See below.) However, while these systems may seem different at first glance, there are ways of reconciling them.

But, seriously, for additional analysis, criticism, and details, read on. Let me explain.

The Three-Stage System

Arguably, the most widely repeated and used classification system is (one version of) a three-stage view of Alzheimer’s decline. It is the one promulgated by the powerhouse Alzheimer’s Association, through its flagship website.[1] And, let’s face it, with only three classification categories, the system is just plain easy to remember.

The standard enumeration of this three-stage system is straightforward.

The Standard, Three-Stage View of Alzheimer’s

- Beginning/Early Stage

- Middle Stage

- End/Late Stage

As I mentioned in my introductory remarks, part of the appeal of this way of categorizing the progression (or, rather, regression) of Alzheimer’s dementia is that it somewhat neatly corresponds to way in which we are used to stories being told.

And, in a sense, this categorization schema basically helps people tell the story of a particular Alzheimer’s patient’s personal struggle with the disease. The immediate utility of the approach is that, upon hearing the stage, one immediately knows where the sufferer is in his or her story of decline – at the start, at the finale, or somewhere in between.

Symptoms map fairly intuitively – even if somewhat vaguely – onto the three stages.

For example, if your loved one needs little to no help with daily living, then he or she would fit most neatly into the “early stage.” As soon as assistance for the so-called “activities of daily living” reaches a predetermined threshold (specifically, lacking two out of six, for more information on which see this ARTICLE and this VIDEO), then for all intents and purposes the person is well into middle stage. The final or “end” stage of the disease occurs when impairment is so severe as to prevent locomotion and, later, cease or impede more basic bodily functions such as coughing and swallowing.

What to Expect at Each of the Three Stages

As the Merck Manual puts it: “In Alzheimer’s disease, parts of the brain degenerate, destroying cells… Abnormal tissues, called senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, and abnormal proteins appear in the brain…”.[2] Because this deterioration may affect different parts of the brain in different sufferers, the symptoms of Alzheimer’s are prone to vary from person to person. However, there are recognizable patterns of changes that are fairly stable.

I will break the relevant changes into four categories: changes affecting cognition, daily living, memory, and personality. Just a word of caution. The categories are not necessarily mutually exclusive; nor are the various symptoms neatly divisible into the categories.

Presently, I will give you a sense of what these four categories of change might look like across the three stages of Alzheimer’s just canvassed.

Changes in Early-Stage

Cognitive Changes in Early Stage

As Alzheimer’s begins, high-level changes are minimal. Most function remains intact, but there are a few areas of concern.

Number one, sufferers in early stages of Alzheimer’s may begin to experience difficulty with so-called “abstract thinking” – that is, thinking about ideas and abstract objects (e.g., numbers, propositions, sets). They may therefore have trouble with such activities as doing mathematics problems or otherwise manipulating numbers. It is, however, vitally important to take a person’s “baseline” into account. In other words, a person’s present abstract-thinking abilities must be assessed against the abilities that they had five years ago, ten years ago, etc. The pertinent thinking difficulties are relative to an individual’s prior capabilities.

Number two, early-stage Alzheimer’s patients arguably start to lose some of their language faculties. But as this is first and foremost evidently a memory problem, I will cover it below.

Daily-Living Changes in Early Stage

In such fields as long-term-care insurance and senior healthcare, one important concept is the definition of the “Activities of Daily Living,” or ADLs.[3] I go into much greater detail on the ADLs in THIS ARTICLE and THIS VIDEO. Suffice it to say that there are six of them – bathing oneself, dressing oneself, feeding oneself, maintaining one’s continence, toileting by oneself, and transferring in and out of bed by oneself – and that losing the ability to perform two out of the six qualified a person as “long-term care” needy. Additionally, having diminished cognitive capacity – and requiring supervision – can also trigger the need for long-term care.

As far as the ADLs go, early-stagers are usually in pretty good shape. At least, they’re not too badly off in terms of their mental decline. It is always possible that a given patient also sufferers from ailments, conditions, or diseases in addition to Alzheimer’s and that these comorbidities affect the person’s ability to perform one or more ADLs quite separately from the dementia.

In the early stage, many Alzheimer’s-afflicted individuals can or will still enjoy some measure of independence. They are frequently still able to perform the ADLs and their sleep patterns remain largely unaltered by their conditions.

Memory Changes in Early Stage

As noted, above, some there are sometimes hints of looming language problems in early stage. However, these are often confined to the remembrance of things like names and other words. It is sometimes said that early-stage dementia sufferers have a word on the tips of their tongues, as it were, but are unable to bring it back.

Patients may also forget instructions or plans, and they may lose items.

Personality Changes in Early Stage

Now if you are breaking into cold sweats looking at the list of changes, thinking, “Oh, no! I Forget words and lose objects and struggle to do math… I must be in the early stages of Alzheimer’s!” Take heart.

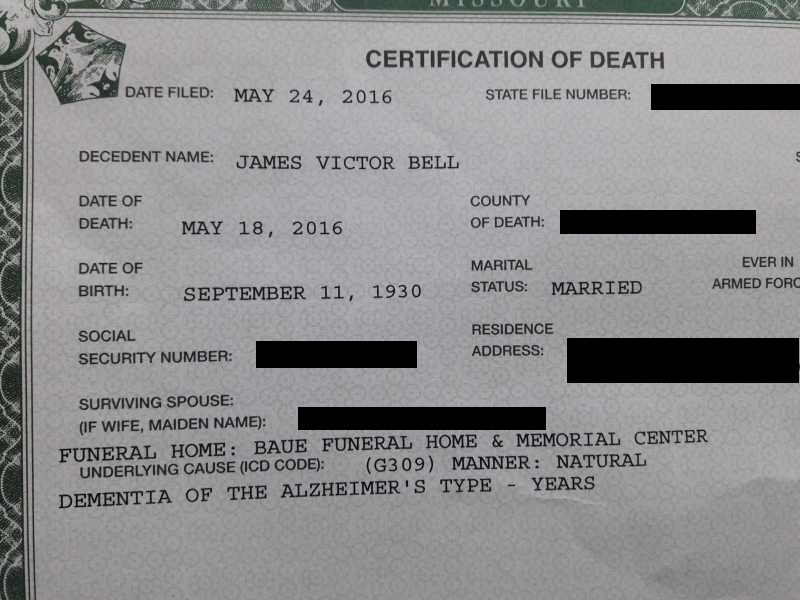

For this final category of change is often the one that makes the presence of dementia the most apparent – and poignant. This is the group of changes that affect a person’s personality. My dad, Jim, for instance, was always the sweetest guy. But as his Alzheimer’s progressed, he became belligerent, suspicious, and unpleasant. (Read about Jim’s experiences HERE.)

In early stages, however, changes may not yet be that dramatic. A person may simply become somewhat more awkward in social situations than he or she had been previously. Or certain – possibly latent or recessed – personality tendencies may suddenly start to get more pronounced.

Changes in Middle Stage

Cognitive Changes in Middle Stage

During middle stage, language abilities take a major hit. Reasoning processes become more muddled.

Other cognitive changes dovetail with personality changes, about which read more further on.

Daily-Living Changes in Middle Stage

The sufferer’s abilities to perform the ADLs also declines sharply through middle stage. The affected individual may bathe infrequently and inadequately, for instance. And the person may begin to behave erratically and unreliably in the bathroom.

To illustrate, my dad would sometimes confuse various paper products – facial tissues, paper towels, toilet paper, etc. – with potentially messy results that I will leave to readers’ imaginations.

The capability of dressing oneself may or may not remain. In some cases, the mechanical ability to put on clothes is present, but – because of decreased awareness, judgment, and so on – a person loses the good sense to choose appropriate garments for the occasion or for the weather.

Sleeping may also begin to go haywire. My dad would often be awake late into the night, and he would frequently nap at odd times during the day. Some of this might be treatable with sleep aids or coffee.

Memory Changes in Middle Stage

As the Alzheimer’s worsens, sufferers begin to have difficulty remembering personal information – address, social-security number, telephone number, and so on. They will also tend to have trouble recalling newly acquired information and recent events.

A person may also begin to “elope” from his or her residence and wander around. In my dad’s case, it sometimes seemed to me that he was “testing” his memory by leaving and seeing if he could find the way back. However, it is also possible that he (and other patients) merely begin to leave with some poorly conceived plan or purpose but then forget those things along the way and end up roaming about aimlessly.

Personality Changes in Middle Stage

At this stage of things, a personality might have diverged considerably from what family and friends were used to. The nature of these changes is prone to variation. But anecdotally, I have found that numerous caretakers and relatives relate that their loved ones either became more aggressive or docile than they had been. My dad became the former.

Still, many Alzheimer’s sufferers will be moody, and their demeanors will shift – sometimes without much warning.

Alzheimer’s-affected people may withdraw entirely from social interactions. And they may be delusional or even paranoid. I have frequently related that my dad accused my children and me of stealing from him (among other allegations).

Excursus: Ambulation, Family Recognition, and ‘Sundowning’

Somewhere in the hazy nexus between middle and late stages, three other things may become issues for your loved one – as they were for my dad.

Ambulation

“Ambulation” is a ten-dollar word for “walking.” In my dad’s case, as his Alzheimer’s progressed – and, frankly, as his nursing-home caretakers more heavily medicated him – he lost the ability to “ambulate.” He became “non-ambulatory,” meaning that he went from being able to walk around to being unable to do so.

This is a considerable and serious change. This is so not only because of the diminishment of the faculties and personal independence that it represents, nor even because of the terminal stage that it portends – which is scary, indeed. (On Alzheimer’s as a terminal illness, see HERE.) But the loss of mobility also increases the patient’s risk for secondary health problems such as blood clots and pneumonia.

Family Recognition

Another striking facet of this murky degenerative process is the ultimate obliteration of an Alzheimer’s sufferer’s ability to recognition close family and friends. Whether this is based upon the destruction of a person’s memories regarding faces, voices, and personalities or whether it is grounded in something else (e.g., a malfunctioning perceptual apparatus, or awareness gone berserk) is unknown. But, at some calamitous and sad point, it appears as though certain Alzheimer’s sufferers will lose their abilities to even acknowledge or identify people who were – and are – of great importance in their lives.

‘Sundowning’

“Sundowning” is a rather odd phenomenon that my family was introduced to after my dad was in the hospital for triple-bypass surgery. It refers to a condition – likely a byproduct of the changes brought on by Alzheimer’s – whereby a person becomes more confused as the day progresses. In other words, some dementia sufferers are more difficult to handle and more disoriented in the evening hours than they are earlier in the day.

Whether this has anything to do with sunlight exposure is unknown. But for an intriguing link between Alzheimer’s Disease and vitamin-D deficiency, see HERE and HERE.

Changes in Late Stage

Cognitive Changes in Late Stage

Perhaps the most tragic change to occur in late stage is that communication dwindles to virtually nothing. In some cases, an Alzheimer’s sufferer may seemingly become totally unresponsive to external stimuli.

Daily-Living Changes in Late Stage

Changes in this category escalate dramatically. Many times, in late stage, ability to perform any of the ADLs drops away entirely. To put it slightly differently, and due to compromised fine-motor skills, patients lose the ability to self-dress.

The also tend to lose the ability to feed themselves. And this occurs as a gloomy precursor to the loss of even more basic life functions, such as the ability to swallow food and water.

Moreover, late-stage Alzheimer’s patients typically experience near complete degradation of their mobility, to the point where they can no longer transfer in and out of bed on their own power. Indeed, many individuals lose the ability to even do something as simple as sit upright.

In this end phase, infections (like pneumonia, sepsis, and urinary-tract infections) become all too common. Sometimes death comes through these – or similar, attendant conditions like blood clots.

For more information on how Alzheimer’s sufferers die, as well as on what constitutes a “terminal illness,” see articles HERE and HERE, as well as THIS VIDEO.

Memory Changes in Late Stage

At this point in the process of devolution, memory is seriously eroded or otherwise undermined. The patient may only recall distant memories, if even those. Basic awareness and perception are either extremely weakened or entirely absent.

Personality Changes in Late Stage

Even the exaggerated and somewhat caricatured personality traits of the succeeding stages melt away into oblivion. It can feel as though the person you knew has essentially disappeared.

Affect is often flat, and your loved one may (appear to) be completely emotionless.

Caveat: Categorization Is Not an Exact Science

However, as I have stated elsewhere (see my brief overview of Alzheimer’s, HERE), there is not a little guesswork that goes into actually categorizing a person into a stage. Citing “overlap,” the Alzheimer’s Association warns readers to be mindful of the fact that “…it may be difficult to place a person …in a specific stage…”.[4]

One problem is really ambiguity or “fuzziness” in the in-between areas.[5]

So, for instance, based solely upon mini-cognitive examinations (for a bit more on which, see this ARTICLE and this VIDEO) it may be somewhat difficult to say when, precisely, a person goes from simple, age-related forgetfulness to clinical impairment or dementia.

There are a number of possible reasons for this imprecision. If you’re interested in my opinion, you can read a few of my speculations in the APPENDIX at the bottom of this page. They may give you a sense of what I believe to be the complexity inherent in this issue. If you’re not interested – and that’s okay! – then just keep moving down to the next section, where I get into enumerations of the seven-stage view.

The Seven-Stage System

As just previously noted, the whole Alzheimer’s-classification thing is sort of fuzzy around the edges. (For more commentary on this, see the “Appendix,” at the bottom of the page.) In fact, as has been alluded to, even the choice of schema leaves not a little bit to personal (or professional) preference. However, this is probably to be expected, given the incomplete state of our knowledge about the disease. (For an overview of Alzheimer’s, see HERE.)

This is not meant to be an indictment of the categorization process. But it is something I think that you should be aware of.

Dissatisfaction With the 3-Stage View

Some people have apparently been dissatisfied with the three-stage view. The most intuitively obvious criticism of the three stages might be that they paint with too broad a brush. To put it another way, Alzheimer’s is a disease that causes brain and cognitive degenerative over years, or even over decades. The changes can be somewhat gradual. Some people might worry, then, that a categorization system that only uses three stages might be a bit too clumsy and overly general to apply to such a lengthy process of deterioration.

With only three stages, an Alzheimer’s-afflicted person must fit into one of the three. But you may find people with widely varying abilities and deficits sharing the “same stage.”

For example, even though the transitions are hard to pin down, a person who has just entered “middle stage” will be a little worse than (but still somewhat close to) a person who is still in “early stage.” But a person whose regression is getting so severe that he or she is about to enter “late stage” will be much worse off – and yet will still be in “middle stage.”

The result is that you can have two people – both in “middle stage” – who have very different sets of abilities and needs. And this might seem to be a poor way to classify patients.

And this same problem can probably be retooled to apply to all three of the stages. For instance, my dad basically went through the entirety of “late stage.” At the beginning of this stage, he had pretty well lost the ability to communicate and walk and he was nearly continuously struggling with some infection or other. But, by the end, he lost the ability to swallow food and water and, eventually, was only able to lie in bed, having lost the ability to sit upright. He looked very different at the beginning of late stage and at the end of it. So, again, the question is: Is it really meaningful to think of both as being the same stage?

7 Stages as a Modification to the 3-Stage View

Now, one possible way to salvage the three-stage view would be to start referring to grades within each stage. So, instead of speaking about “middle stage, [period],” you might talk instead of “early-middle stage” or “late-middle stage.” So, for instance: My dad, sitting and smiling, but unable to talk or care for himself was in “early-late stage.” But my dad lying there, unable to swallow food or water was in “late-late stage.” Or something like this.

But by this time, a person might reasonably ask: do we really have a three-stage view anymore? If you are going to add qualifiers to every stage, why not just carve out a few more stages?

I am not entirely clear on the history, here, but presumably, the seven-stage view was an outgrowth of this kind of reasoning process.

Even here, though, variations abound. Just as with the three-stage view, the seven-stage system has its variants as well. (See further down this post for the details.) My research suggests that when a seven-entry catalog is used, it generally represents the stages as follows.

The Standard, Seven-Stage View of Alzheimer’s

- No Impairment

- Very Mild Decline

- Mild Decline

- Moderate Decline

- Moderately Severe Decline

- Severe Decline

- Very Severe Decline

This articulation of the stages was apparently devised by academics Barry Reisberg and Emile Franssen[6] and seems to be preferred by authority sites such as Alzheimers.net.[7] Additionally, it is repeated, or reproduced on a website called CaregiverHomes.[8]

And the seven stages are presumably supposed to give us a bit more precision in classifying a person into a stage. However, as with the three-stage view, it may not always be totally clear in which of the seven stages, exactly, a given patient falls. But let’s look at what the seven-stage view adds.

Differences Between the 3- & 7-Stage Views

The first addition is a stage dedicated to a state of “no impairment.” This may seem somewhat strange, since it implies that – on this particular scale – everyone is at least in “Stage 1” of Alzheimer’s. I’m not entirely sure that I find it helpful to include a category that – as far as I can tell – basically doesn’t distinguish between a normal 65-year-old who will, as it turns out, develop Alzheimer’s in ten years and a newborn baby who won’t develop any sort of dementia for decades (if ever).[9]

Skipping Stage 2 for the moment, I note that the inclusion of a Stage 3 seems more understandable. In an alternative exposition of the seven stages (see the relevant section, below), “Mild Decline” is identified with a condition that has come to be known as “Mild Cognitive Impairment,” or MCI. According to standard opinion, this condition is actually diagnosable by a doctor and it is often a prelude to full-blown Alzheimer’s. Therefore, it makes some sense to include it as a “stage” of Alzheimer’s – even though it is by no means certain that a person with MCI will develop Alzheimer’s.

One Mayo Clinic article flatly declares that MCI “may increase your risk of later developing dementia caused by Alzheimer’s disease or other neurological conditions. But some people with mild cognitive impairment never get worse, and a few eventually get better.”[10] Some commentators speak merely of the “likelihood of progression from MCI to Alzheimer’s,”[11] which implies that the link is one of probability as opposed to inevitability.

So, even though the inclusion of this Stage 3 makes some sense, it is still a bit puzzling. After all, if you have a diagnosis of MCI it may be misleading to think of yourself as being in “Stage 3 of Alzheimer’s” if it is true that you may never develop Alzheimer’s – or even that you may improve.

Stage 2 is also a little peculiar. According to presentations of the seven-stage system, Stage 2 is unlikely ever to be recognized while a person is in it. For example, in the explanation of this stage given by the folks at Alzheimers.net, we read that “the disease is unlikely to be detected by loved ones or physicians.”[12]

You have to realize, therefore, that the seven-stage system has several listed stages that you will probably only be able to assign to yourself or your loved one in retrospect.

Take my dad’s case. My dad, Jim, wasn’t diagnosed with Alzheimer’s until he was in middle stage – on the three-stage view. Assuming that, in seven-stage lingo, he had “moderately-severe decline” by this time, he would have been at (or around) Stage 5 on the longer scale.

To put it differently, my dad’s Alzheimer’s wasn’t recognized right away. Thus, it is important to note that regardless which of the two scales you prefer, my dad’s Alzheimer’s advanced with at least one stage being unnoticed.

The only thing that I would say is that it seems on the three-stage view, it would have theoretically have been possible to actually identify my dad as having been in “Early Stage Alzheimer’s” while he was in it. Granted, it was missed in my dad’s case. But this wasn’t a deficiency of the scale. It was a deficiency of the observers, who failed to recognize or properly identify the signs.

On the other hand, on the seven-stage system, it appears as if Stage 3 is the earliest stage that could actually be recognized for what it is — at least, while a person is in it. And, as we have seen, Stage 3 may not progress into Alzheimer’s at all.

To summarize the additions we’ve addressed so far:

- Stage 1 applies to everybody who isn’t already classified in a higher stage.

- Stage 2, practically by definition, will go unnoticed.

- Stage 3 may be noticed but may not actually develop into Alzheimer’s.

But this seems to mean that the first three stages of the seven-stage system arguably don’t add much of use to the three-stage system.

Stage 4 gets us into bona fide Alzheimer’s. But, by this time, the patient would likely be in “early stage” on the three-stage system.

Once we get to this point, the sevenfold taxonomy now provides us with four stages (4, 5, 6, & 7) for categorizing patient’s Alzheimer’s status. Apart from the first three stages, which may or may not be of interest, this additional stage does seemingly give the seven-stage view an advantage over its three-stage counterpart.

How the Three- and Seven-Stage Systems Fit Together

Logically (if not chronologically or historically), the usual way of unpacking seven stages is perhaps best thought of as an expansion of – or an elaboration upon – the three-stage system.

Indeed, as readers probably noticed, the three stages (from the three-stage list) are pretty obviously included within the seven stages. On this way of thinking about the systems, essentially, the seven-stage view merely adds on four stages to the briefer threefold articulation.

However, these additions and expansions need not be thought to generate an entirely novel or divergent classification system. In other words, there are ways of combining the two systems.

One approach, taken by the aforementioned CaregiverHomes website, is to embed the three stages from the shorter taxonomy into the sevenfold system.

This might look like the following. On the left, I name the relevant stage from the three-stage approach, and then, on the right, I provide the corresponding stage(s) from the seven-stage approach.

- [Stage from Threefold View: NONE (Preclinical Alzheimer’s)→[Stages from Sevenfold View: 1-3]

- [Stage from Threefold View: Early Alzheimer’s)]→[Stage from Sevenfold View: 4]

- [Stage from Threefold View: Middle Alzheimer’s)]→[Stages from Sevenfold View: 5-6]

- [Stage from Threefold View: Late Alzheimer’s)]→[Stage from Sevenfold View: 7]

Are There Alternative Classification Systems?

A Two-Stage System

Theoretically, a simple two-stage schema can be formed by linking the idea of a pre-symptomatic first stage with a symptomatic second stage.

Simple 2-Stage Formula

- Pre-symptomatic Stage

- Symptomatic Stage

It is highly doubtful that such a characterization of the disease is of much use for caretaking or diagnostic purposes. But there may be certain clinical or research contexts in which the only relevant fact is whether a subject is pre- or post-symptomatic.

Alternative Three-Stage Systems

An Expanded Two-Stage Approach

The first alternative to the standard (early, middle, late) three-stage view is basically the simple, two-stage view with an intermediate stage added that allows for stage two to be divided into two parts. (And, maybe there’s one additional little change.)

Sometimes this median stage is designated by the rather cryptic word “prodromal.” The so-called prodromal stage, number one, is that which lies in between the pre- and post-symptomatic stages. But, number two, it is also a particular kind of “symptomatic stage.” Namely, the “prodromal” stage is that in which “memory is deteriorating but a person remains functionally independent.”[13]

So, the initial “symptomatic stage” is therefore also replaced by a stage that complements the prodromal stage. To be precise, the third stage becomes one in which the person is no longer functionally independent.

This version of the three-stage view would look something like this.

‘Functional’ Three-Stage View

- Pre-symptomatic Alzheimer’s

- Prodromal Alzheimer’s – Memory is Negatively Affected, But Person Functions Independently

- Nonfunctional Alzheimer’s – Both Memory and Daily Function are Deteriorated

Three Stages as Losses of Psychological Powers

The ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle (384-322 B.C.E.) wrote a book that has come to us better known by its Latin title, De Anima (ca. 350 B.C.E.), meaning “On the Soul.” In fact, the Greek word for “soul” was psyche (or psuchē). The word persists in our day in our science of psychology – which, to an ancient, would designate the “study of the soul.”

But, just as the science of psychology does not attribute religious or supernatural qualities to the psyche, so too in this work does Aristotle assume a more or less “neutral” definition of “soul.” Stemming back to at least to Plato, psyche basically just meant “life force.”[14] And that minimalistic definition will suffice for what follows.

Aristotle recognized three levels of life force, pertaining to plants, animals in general, and human animals in particular. He distinguished them in virtue of what have come to be called “powers” of the soul.[15]

So, at the level of plant life, Aristotle thought, there was a “nutritive” or “vegetative” soul. This life force was evident in virtue of a plant’s ability to grow, “nutrify” itself – by drawing upon soil, sunlight, and water – and to reproduce.

A bit higher up are the animals, enjoying an “animal” or “sensitive” soul. This life force has all the nutrifying and reproductive abilities of a plant alongside certain locomotive and appetitive powers that allow animals to move from place to place (unlike plants) and to experience sensations.

Finally, there are humans, who have “human” or “rational” souls. As before, the human life force subsumes all the powers of plants and animals – mobility, nutrition, reproduction, sensation, etc. But human beings also have rational faculties that allow us to be capable of reasoning, reflecting, remembering, and so forth.

With that much groundwork in place, I will observe that it is possible to think of Alzheimer’s stages in Aristotelian terms. To be more exact, Alzheimer’s can be thought of as progressively stripping an individual of “soul powers,” so to speak. There are three layers, corresponding to the rational, animal, and nutritive qualities of the human life force, as briefly sketched above. This creates a kind of three-stage Aristotelian view of the decline of Alzheimer’s that can be roughly represented as follows.

3-Stage ‘Aristotelian’(-Inspired) View

- Loss of Rationality – Cognition, Memory, Etc.

- Loss of Animality – E.g., Locomotion

- Loss of ‘Nutritivity’ – Ability to Sustain One’s Own Life & Bodily Functions

Put somewhat colorfully, the basic – and tragic – idea is that Alzheimer’s dementia systematically strips away various physiological-psychological powers, leaving the sufferer without even the basic nutritive capabilities of a plant. It may work better as a metaphor than as a literal description of the effects of the disease, but I think it is evocative.

Alternative Seven-Stage System

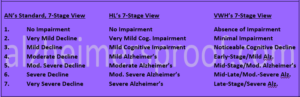

There are several slight variations on the seven-stage system. Each of them shares fundamental similarities, however. For example, the website Healthline (HL) gives a slight variation on the sevenfold enumeration sketched in a previous section.[16] (See above.)

HL’s Alternative Seven-Stage Breakdown

- No Impairment

- Very Mild Cognitive Impairment

- Mild Cognitive Impairment

- Mild Alzheimer’s

- Moderate Alzheimer’s

- Moderately Severe Alzheimer’s

- Severe Alzheimer’s

The first stage – “No Impairment” – is identical to that given by AN. Here, however, the words “cognitive impairment” is used in the second and third stages, as opposed to the employment of the word “decline.” Otherwise, in the first three stages, the systems are in agreement with respect to their adjectives.

At Stage 4, though, we begin to see a few slight differences. In AN’s version, Stage 4 is labeled “Moderate Decline,” whereas HL names the same stage “Mild Alzheimer’s.” I suppose that the idea is that mild Alzheimer’s is characterized by moderate (cognitive) decline, and so these should come down to the same thing.

Similarly, AN’s Stage 5, labeled “Moderately Severe Decline,” is presumably supposed to convey the same idea as HL’s “Moderate Alzheimer’s.” Readers will probably be struck with the fact that these words – including “decline” and “impairment” as well as “mild,” “moderate,” and “severe” – are somewhat artful, as they appear to lack precise diagnostic criteria.

Again, at Stage 6, we may compare AN’s “Severe Decline” with HL’s “Moderately Severe Alzheimer’s.” Apparently, we are to understand that moderately severe Alzheimer’s is distinguished by severe cognitive decline.

Finally, AN’s “Very Severe Decline” apparently corresponds with HL’s “Severe Alzheimer’s.”

Frankly, I can’t help getting the impression that these authors – however well-intentioned – are battling more over English modifiers than they are disputing about Alzheimer’s symptoms. And this impression is underscored when I look at another – basically, identical – list, this one from Very Well Health (VWH).

VWH’s Seven-Stage System

- Absence of Impairment

- Minimal Impairment

- Noticeable Cognitive Decline

- Early-Stage/Mild Alzheimer’s

- Middle-Stage/Moderate Alzheimer’s

- Middle-Stage/Moderate to Late-Stage/Severe Alzheimer’s (sic)

- Late-Stage/Severe Alzheimer’s

The similarities between this list and the previous two are probably not worth tediously rehearsing. It is arguable, though, that the addition of the word “noticeable” in this rendition of Stage 3 is supplied in deference to the fact (stated earlier) that Stages 1 and 2 are pretty much undetectable.

VWH’s list seems to have been drafted to combine the verbiage of the three- and seven-stage systems, possibly in an effort to aid comprehension. (Or possibly just to create feelings of familiarity in people regardless of which system they are accustomed to.)

A Five-Stage System

Believe it or not, there is another way of reckoning the various stages of Alzheimer’s. It comes from the prestigious Mayo Clinic, no less.

“There are five stages associated with Alzheimer’s disease: preclinical Alzheimer’s disease, mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease, mild dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease, moderate dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease and severe dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease.”[17]

Mayo Clinic’s 5-Stage System

- Preclinical Alzheimer’s

- Mild-Cognitive Impairment due to Alzheimer’s

- Mild Dementia due to Alzheimer’s

- Moderate Dementia due to Alzheimer’s

- Severe Dementia due to Alzheimer’s

Actually, since the initial question was “Does Alzheimer’s Have Three or Seven Stages?” it might seem somewhat odd for me to end by saying, “Maybe it has five!” I hope readers have detected by now my skepticism that a definite number of “stages” can be fixed upon. But, the five-stage view – particularly this articulation of it – does have several things to commend it.

Number one, the tag-on line “due to Alzheimer’s,” performs real work. For instance, one criticism against the seven-stage system’s reference to “mild cognitive impairment” was that MCI does not necessarily develop into Alzheimer’s. But, here, the Mayo Clinic writers rebut this by qualifying the sort of MCI that they have in mind. They’re not just talking about any old MCI. They’re talking about MCI due to Alzheimer’s. I don’t know whether MCI can be distinguished like this – in advance, anyway. But it is an admirable attempt to address this sort of criticism.[18]

Number two, the system begins with “Preclinical Alzheimer’s.” This, to my mind, seems a much more reasonable starting place for a list of Alzheimer’s stages than does the sevenfold systems’ mention of a “no-impairment” stage that basically applies to everyone from infants in diapers to high schoolers, collegiates, and basically everyone who isn’t already in a further stage.

Conclusion

I am skeptical that there is a definite – let alone identifiable – number of “stages” that every and all Alzheimer’s patient goes through. I am even skeptical of the lesser claim that there is a fact of the matter about the number of stages that an Alzheimer’s patient would go through if he or she lived through an entire progression of the disease.

Firstly, I just don’t think that Alzheimer’s disease itself works like this. Alzheimer’s is a brain-degenerating disease. And, presumably, it affects different parts of the brain in different people. So, in the first place, it seems plausible to think that a person’s experience with Alzheimer’s – and his or her “stages” of decline – will be highly individualistic or idiosyncratic or however you want to put it. They will be particular to him or her.

Secondly, I just don’t think that words like “mild,” “moderate,” “severe,” or for that matter “stages” are precise enough to do the classificatory work desired, expected, or hoped for. There is a vagueness that attends to each of these. And insofar as the various categorization approaches just string these words together, it seems to follow that there is a vagueness that permeates the whole project.

But this is emphatically not to say that there is not utility to classifying Alzheimer’s patients or to trying to track their declines. There surely is great benefit to this.

So, keep your favored system. Learn about it. Study it. And apply it. Perhaps, though, it would be best not to be doctrinaire about your preferences. It is probably the case that all the systems surveyed are good enough for their own purposes. And many times the purposes for systems will vary.

Appendix

Six Reasons Why It Is Difficult to Pin Down A Stage

- Self-reporting. This is hardly unique to cognitive dementia tests. Rather, it attends – to one degree or other – to virtually any examination that depends upon people talking about how they feel. In a word, people are unreliable. They can be misleading or mistaken – and that’s just for starters.

- Question limitations. Another difficulty lies in the cognitive-examination questions themselves. Questions typically ask about areas of common knowledge, like the days of the week or the letters of the alphabet. However – and I am no neuroscientist – it seems to me that insofar as Alzheimer’s is characterized by brain deterioration, and insofar as different areas of the brain might be affected in different patients, it may be that some patients’ impairments will not be identified by these sorts of questions. Possibly this will be because parts of their brains are impacted other than the parts that store the answers to these questions.

- Alternating lucidity and murkiness. Another factor is that Alzheimer’s sufferers typically swing from periods of clarity to periods of cloudiness. From interacting with my dad, Jim, I remember that there will be times when he would not be able to answer a particular question that would be followed by times where he would be able to. And this cycling can go on for many years. One reason why Jim’s physician didn’t recognize his Alzheimer’s as early as would have been desired was probably due to this very fact. My dad just happened to be more lucid during doctor’s appointments than he was when it began to be apparent to the family that something was off.

- Lifestyle variations. And this, it seems, sort of segues into another possibility difficulty. Namely, different people live different types of lives and surround themselves with different types of people. Whereas, in the year or so before my dad was officially diagnosed, I had the opportunity to observe him closely – and I had the ability to research Alzheimer’s symptoms and compare them with my dad’s behaviors – other Alzheimer’s sufferers may not live or interact with people who are able or willing to perform similar roles for them. Things can go unnoticed, unrecognized, or neglected.

- Baseline differences. Yet another sticky area involves the intuitive fact that people have different vocabularies and levels of intelligence. If this is so, though, then it’s not enough to say that a person’s cognitive abilities are at some particular level, say “level x” (whatever x happens to be). To get a truer picture, observers must actually be able to compare the subject’s cognitive abilities against his or her baseline – that is, the cognitive level that he or she was at before any (suspected) impairment surfaced. But this assumes a level of personal knowledge and past dealings between observer and subject that may not exist.

- Vague diagnostic categories. Finally, and I am no medical professional, but it also seems to me that there is a bit of fuzziness built into the lists of symptoms to watch out for. The Alzheimer’s Association, for example, says that early-stage Alzheimer’s will be characterized by things like a person struggling to “[come] up with the right word or name” in a given situation or “[l]osing …a valuable object”.[19] Firstly, and surely, these symptoms comes in degrees. But, secondly, qualifier such as “right” and “valuable” are not a little vague themselves.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m not saying that the diagnostic situation is hopeless. I’m simply suggesting that it is difficult. It’s not easy to say, on the basis of cognitive tests alone, that a person has or doesn’t have the beginnings of bona fide dementia.

Fuzzy at the Edges; Clearer in the Center

These problems of vagueness abound in language, philosophy, and psychology. To hearken back to the discussion I had HERE, perhaps the best we can say is that even though stages might be fuzzy around the edges, things are clearer in the middle.

By way of illustration, the predicate “tall” is somewhat vague. After all, who can say what the precise cutoff is between being tall and not being tall? Is the cutoff between precisely at 6’? 6’5”? Where is it? The answer – if there is one – is hard to give.[20]

But whereas we may feel uncomfortable stating a cutoff, most of us would not hesitate to say that Perter Dinklage (4’4”) is not tall, but Shaquille O’Neal (7’1”) is. If this is the case, then it tends to show that we don’t have to have a perfectly identifiable cutoff in order to recognize clear-cut cases.

To apply this, we simply get comfortable with the notion that even though I can’t say for sure when my dad developed full-blown early-stage Alzheimer’s, we are comfortable saying that by 2008, he was in middle stage. He was clearly in middle stage. Similarly, by 2016, he was clearly in late stage. And I can say this even though I have no idea when he transitioned from middle to late stage.

Notes:

[1] See n.n., “Stages of Alzheimer’s,” Alzheimer’s Association, n.d., <https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/stages>.

[2] Robert Berkow, et al., eds., “Delirium and Dementia,” The Merck Manual of Medical Information, Home Ed., New York: Pocket Books, 1997, p. 366.

[3] Technically, it should probably be the AsDL, but that looks and sounds awkward. Let’s never speak of it again.

[4] “The Stages of Alzheimer’s,” Alzheimer’s Association, loc. cit.

[5] Just to give it a name, let’s call that “liminal uncertainty,” or LU for short.

[6] inally, Dr. Barry Reisberg of New York University Medical School’s Alzheimer’s Disease Center for Cognitive Neurology, along with and Emile Franssen. They called their stages: “Normal,” “Normal Aged Forgetfulness” (a concept that seems to me to be reminiscent of V. A. Kral’s “benign senescence”), “Mild Cognitive Impairment,” “Mild Alzheimer’s Disease,” “Moderate Alzheimer’s Disease,” “Moderately Severe Alzheimer’s Disease,” and “Severe Alzheimer’s Disease.” See “Clinical Stages of Alzheimer’s Disease,” An Atlas of Alzheimer’s Disease, Mony de Leon, ed., Encyclopedia of Visual Medicine Series, New York: Parthenon, 1999, passim.

[7] See “What Are the Seven Stages of Alzheimer’s Disease?” Alzheimers.net, Jul 8, 2018, <https://www.alzheimers.net/stages-of-alzheimers-disease/>.

[8] See Angela Stringfellow, “The 7 Stages of Alzheimer’s Disease: What to Expect From Preclinical Alzheimer’s Disease to End-Stage Alzheimer’s,” CaregiverHomes, Oct. 12, 2017, <https://blog.caregiverhomes.com/the-7-stages-of-alzheimers>.

[9] True, in some presentations, “Stage 1” is limited to adults. So, Carrie Hill, writing for VeryWellHealth in an article titled “The 7 Stages and Symptoms of Alzheimer’s Disease,” states that Stage 1 describes “a normally functioning adult,” Jun 26, 2018, <https://www.verywellhealth.com/alzheimers-symptoms-98576>. Firstly, even so, assuming that we reckon adulthood from legal emancipation – let’s say between the ages of 18 and 21 – that leaves quite a spread. Do we really want to say that a normal, healthy 22-year-old college graduate has “Stage 1 Alzheimer’s”? But, secondly, concerning “Stage I: Normal,” Barry Reisberg and Emile Franssen – both credited with the initial and presumably authoritative articulation of the sevenfold taxonomy – write: “At any age, persons may potentially be free of objective or subjective symptoms and functional decline and also free of associated behavioral mood changes. We call these mentally health persons at any age, stage 1, or normal.” (Italics supplied.) From Reisberg and Franssen, op. cit., p. 11.

[10] “Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI),” Mayo Clinic, Aug. 23, 2018, <https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/mild-cognitive-impairment/symptoms-causes/syc-20354578>.

[11] “Mild Cognitive Impairment,” Memory and Aging Center: Weill Institute for Neurosciences, Univ. of Cal. – San Francisco, n.d., <https://memory.ucsf.edu/mild-cognitive-impairment>.

[12] “What Are the Seven Stages of Alzheimer’s Disease?” Alzheimers.net, op. cit.

[13] “Frequently Asked Questions : Prodromal Alzheimer’s,” Glasgow Memory Clinic, n.d., <http://glasgowmemoryclinic.com/faqs/prodromal-alzheimers/>.

[14] This, by itself, by no means implies that there are no such things as “souls” in the more conventional, spiritual/religious sense. But, such a discussion lies well beyond the scope of the present work. I simply wish to make it clear that this portion of the text does not depend in any way on spiritual or religious conceptions of “soul”/psyche. There is a kind of neutral sense, as I state in the main text.

[15] For the bird’s-eye view, see S. Marc Cohen, “Aristotle on the Soul,” Univ. of Washington, Sept. 23, 2016, <https://faculty.washington.edu/smcohen/320/psyche.htm>.

[16] See “What Are the Stages of Alzheimer’s Disease?,” Healthline, n.d., <https://www.healthline.com/health/stages-progression-alzheimers>.

[17] Staff writers, “Alzheimer’s Stages: How the Disease Progresses,” Mayo Clinic, Dec. 12, 2018, <https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/alzheimers-disease/in-depth/alzheimers-stages/art-20048448>. The author or authors go on to define “[d]ementia” as “a term used to describe a group of symptoms that affect intellectual and social abilities severely enough to interfere with daily function,” ibid.

[18] I am certainly not saying that the Mayo Clinic staff formulated in reply to my criticism!

[19] “Stages of Alzheimer’s,” Alzheimer’s Association, n.d., <https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/stages>.

[20] It may even be that there is a certain irreducible relativity. Maybe we shouldn’t speak solely of being “tall” – period – but, rather, being “tall for a [blank],” where the [blank] stands in for some role or profession. So, maybe we should not say that so-and-so is either “not tall” or is “tall” – full stop. For maybe we should only say that he or she is “not tall for a basketball player” or is “tall for a lawyer,” etc. But let’s just forget about this, presently.