Introduction

Alzheimer’s – and other forms of dementia – are menacing and oppressive diseases.

First and foremost, they take their toll on those who are directly afflicted.

But they can – and do – cause much wider-spread devastation.

Those who have seen it “up close and personal,” know this can include financial, physical, relational, and – for those so-inclined – even spiritual fallout.

I have gotten – and will get further – into those angles in other videos.

But among the myriad negative effects are the various emotional and psychological consequences associated with Alzheimer’s – and with dementia caregiving.

Some of these are widely discussed. At least… they’re addressed in general terms, abstractly.

But there’s an issue that tormented me, personally. Reading comments on some of my videos – especially “When Is It Time For a Nursing Home?” – it seems that I’m far from the only one.

So, in this video, I want to talk about what to do when your caregiving efforts drive you to agonize over the question: Does this make me an awful person?

Caveats

I am not a counselor, psychologist, therapist, or anything close to these. And I am not a healthcare provider or medical practitioner of any kind. Therefore, I cannot diagnose mental- or physical-health conditions, and I am unable to give specific personal advice. If you have depression or thoughts about self-harming or anything in those vicinities, you need to seek professional help. This video is intended for general educational or informational purposes only. I am speaking solely from my own experiences and reflection. And my aim is to raise awareness of these issues as well as foster feelings of solidarity among other caregivers and sufferers. The message is: You’re not alone if you feel this way or have these concerns and doubts.

Ten Reasons Why Being a Caretaker Can Make You Feel Like a Terrible Person

This will be rough-going. I’m going to try (!) not to linger on any point – but just sketch them. As always, your comments are welcomed, especially since it’s a good bet that I missed something.

#1 Missing the Signs of Dementia

If you’re like me, you may have a tendency to punish yourself for not having recognized the evidence of Alzheimer’s, or for misinterpreting the signs that you did see. This may or not be the first thing that prompts you to feel rotten. But, thinking back over my caregiving experience, it was the first thing that I thought of.

As I have explained in several videos, my mom seems not to have recognized my dad’s dementia at all. When I came into the picture, I knew immediately that something was wrong.

But I didn’t understand what I was witnessing. Frankly, I thought my dad had turned into a jerk.

It’s easy to feel bad for thinking ill of him. In retrospect, the temptation is strong to regret not being more intuitive or perceptive or for lack of knowledge.

But REALIZE: Alzheimer’s is a tricky disease. And (as I explained in a past video), even doctors can fail to see the writing on the wall. So don’t beat yourself up! We’re not omniscient, after all.

# 2 Being Unable to Help Them

A major and continual problem is our seeming inability to provide meaningful assistance.

When your loved one is struggling to remember an event or name, you may be unable to convince them of an answer that you know to be correct. And you’ll feel like a failure.

REALIZE: It’s not like helping a non-afflicted person remember something they’ve temporarily forgotten. A normally functioning person can know they’ve forgotten something and, after it’s been brought back to their attention, they can remember what they’re forgotten. Alzheimer’s Disease literally destroys the brain. At some point, a cognitively impaired person may no longer have the forgotten memory or any means to retrieve it.

Even more, we’re powerless to stop the advance of dementia. This is obviously a deeply distressing fact. And even though Alzheimer’s is only one of numerous terminal illnesses, it – and cognitive disorders like it – don’t just kill the body. They kill the mind and the personality.

It’s gut-wrenching when your loved one doesn’t recognize you, or repeats over and over that they wanna go home, when you’ve gone above and beyond to give them a caring environment.

FURTHER REALIZE: That just your calming voice or loving touch is helping them at some level. Yes, you feel terrible when you make a loving home-care environment, but it goes unacknowledged. And, it’s true, once their impairment is far-enough advanced, they probably won’t be able to appreciate your efforts. The most important thing, however, is that you provide an objectively loving, safe, and secured space for them – not that they are aware of your efforts.

#3 Calling in ‘Authorities’

Alzheimer’s sufferers may have outbursts. Some might sob uncontrollably. Others may laugh inappropriately. It’s easy to become distraught when you’re unable to calm or comfort them.

My dad was at the opposite end of the emotional spectrum. He frequently exploded in anger. I had to physically restrain him on one occasion. Just what do you do when things get heated?

I once called a well-known dementia-care support group (that’ll remain nameless). And I asked them this question. Believe it or not, the advice I was given was: Call the police!

…which – after my dad’s next nasty outburst – I actually did.

I’ve no clue whether this suggestion reflected an organizational policy or was just the quirky opinion of the person who happened to answer the phone that day. And I’m not saying the step is never warranted!

But, in my case, the ensuing encounter was thoroughly discouraging – and the intervention was revealed to be obviously unsustainable.

Oh, sure, dad settled down at that moment. But I was made to understand – in no uncertain terms – that the police department had neither the manpower nor the training to be home-care “orderlies.” And it’s not like my dad “learned some lesson” or would even remember the episode.

REALIZE: You do what you can with the data you have. I like to draw an analogy with the daily forecast. If you plan your activities around the expectation of sunny skies – and you did your due diligence: checking the radar and weather report, etc. – and it ends up raining, it’s not your fault. Sometimes the best information available to you is just plain wrong.

Another aspect of this isn’t quite as dramatic. It has to do with your loved-one’s doctor.

As I noted elsewhere, physicians often depend on family members to know that something is wrong with a loved one. In my case, I wrote to my dad’s primary doctor letting him know that my mom, my sister, and I were all extremely worried – especially about the issue of his driving.

Specifically, I had to push the doctor to write a report that resulted in dad’s license being revoked. And that felt really lousy. – like I was going behind my dad’s back and betraying him.

What I had to REALIZE, there, was that other people’s lives and wellbeing were at stake. It wasn’t simply about my dad and his autonomy.

What if he confused the brake and the gas pedal while at our local park? – with families walking everywhere and little kids bike riding, playing, and running all over the place?

No. I felt that – as unfortunate as it was – it had to be done. And, ultimately, it wasn’t me doing anything to my dad; it was the Alzheimer’s Disease that was to blame.

#4 Being Embarrassed by Them

But, of course, when your loved one loses their mobility – or has their autonomy restricted, that doesn’t necessarily mean they simply become homebound shut-ins. – At least, not until the dementia becomes really physically debilitating.

It probably means that you have to pick up the transportational “slack.” And this may not simply range over doctor’s appointments.

If you’re in the position of having to assume caretaking all by yourself – and see my recent video – then you might have to cart them along: As you go shopping and run other household-related or personal errands.

And even if you’ve got help on those fronts, your afflicted loved one will need haircuts. Maybe they gain or lose weight and need to try on new clothes.

You might even want to include them in enrichment or leisure activities. My dad always enjoyed outdoor theater during the summer. My mom and dad had their favorite restaurants. And so on.

But, this can give rise to awkward situations. For instance, I was present at a church service during which my dad caused an obscenity-laced disruption. Several times, he caused a “scene” at local stores. He even picked a fight with a relative during a family reunion over some slight – whether real or imagined – that apparently went back decades.

These sorts of experiences can make you not want to be seen with them in public or take them outside at all.

REALIZE that your loved one may benefit from interpersonal interactions. But, sometimes, events are too busy or loud for a person with dementia. They may easily become overstimulated or overwhelmed. So, if possible, choose events and places that are calm and relaxing.

But what can you do about feeling embarrassed? Firstly, it’s totally understandable. Just ask parents of unruly kids.

Something else that I wish I had done more frequently was to alert people around me about my dad’s cognitive problems. There is one way to do this without making a fuss – and without having to say anything out loud that your loved one might not take well.

Namely, there are little business-card-sized announcements displaying text such as: “The Person I’m With Has Dementia. Please be patient. Apologies for any inconvenience.”

In my experience, most of the time, when bystanders react negatively, it’s because they think that a person who is behaving badly is freely choosing their actions. If you can alert people around that something is wrong, they are often much more forgiving.

#5 Losing Patience With Them

Speaking of this, it’s not always easy for caretakers to remain calm, either. And there’s certainly no shortage of composure-testing situations that can arise in a home-care context.

Providing daily care – including supervision – can become monotonous and tedious. Depending on your demeanor, one of your constant struggles might be losing your temper.

It’s easy to become impatient when you have to say the same things over and over.

Again, child rearing is similar in this regard. But, with kids, at least they’re small and are acquiring the capacities to learn and remember. – Not so with a dementia-afflicted adult.

REALIZE that you might not be able to handle caretaking all by yourself. At some point, you might need to seek assistance. This might mean that you have a heart-to-heart with relatives and ask them to step in – whether temporarily or on an ongoing basis.

But it might also require that you consider professional-care options. As I’ve discussed elsewhere, respite facilities exist to offer family caregivers “breaks” on a short-term basis. And, of course, nursing homes may be the only viable long-term alternatives to home care.

#6 Feeling Your Loved One Is a Burden

Another way to say this might be that you find yourself resenting their decline. I mean…

It’s justifiable, and natural to lament your loved one’s cognitive and physical deterioration.

But what I have in mind is different. It’s that you might find yourself becoming bitter at all the time you have to spend attending to their needs. Or you may develop a “grudge” over the fact that your loved one is unable to appreciate – or understand – your predicament and sacrifices.

Relatedly, you might get depressed – or panicky – at the emotional, financial, or physical strain. This may well include having to take leave from a job and, essentially, to put your life on hold.

REALIZE that you’re only human. Your capabilities and your resources are finite. It’s important – vital even – not to make rash choices. If you find yourself down in the dumps after an especially trying week – or month – then try to give yourself a bit of space.

That’s easier said than done, of course. But, as I have discussed in past videos…

…most recently, the one titled “Is It Possible to Be a Caretaker All By Yourself?” …

…there are a few options available to help you. I’ll defer to some of my other presentations for the details. But you may be able to secure what is called “Respite Care.” This is short-term assistance designed for the sole purpose of giving primary caretakers a much-needed break.

Sidelight: Know (Or Discover) Your Limits

At a certain point in time – it does no good for you to press too far beyond your reasonable limits. I choose my words very carefully. There are three key phrases or terms, there.

“A certain point in time,” “too far beyond,” and “your reasonable limits.”

At the end of the day, only you (and your family) can determine, hopefully in consultation with each other, with friends, and with trusted advisers – like doctors, financial advisers, lawyers, etc. – what these points and limits actually are.

But the flip side of making a hasty decision when you’re temporarily or uncharacteristically emotionally low, is disregarding – or refusing to think about – your limits.

And that can land you in extremely dangerous territory. One sign of this might be, …

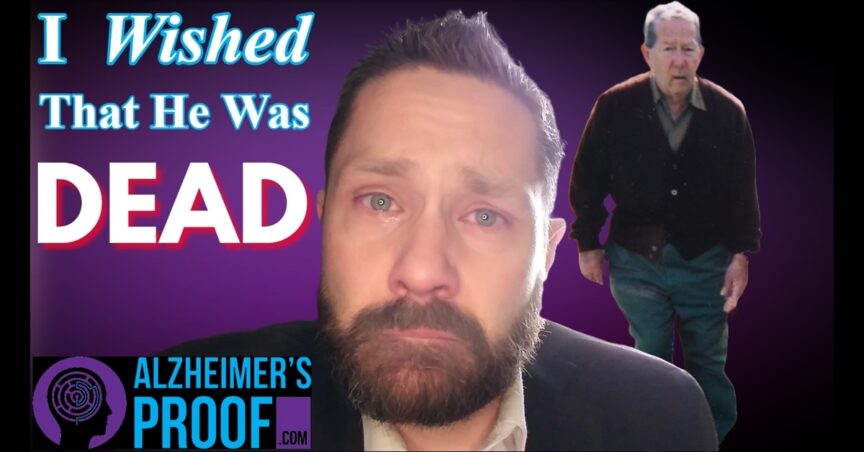

#7 Wishing Your Loved One Would Die.

Or wishing that they were already dead. Let’s draw a few distinctions.

Number one, there’s a difference between (on the one hand) lamenting that your loved one is suffering – focusing on their pain for their sake – …

…and (on the other hand) worrying about their pain because of how upsetting it is for you. – whether for you to deal with, or for you to witness at all, or… whatever.

My dad wasn’t diagnosed with Alzheimer’s Disease until the summer of 2009. Immediately preceding that diagnosis, my dad had had two major surgeries just a couple months apart.

On the eve of the first – a triple bypass – my dad was literally on death’s door. Those surgeries prolonged his life for seven years, as it turned out.

But, it’s easy to ask: For what?! Those years were dominated by cognitive decline. I spent four of them caring for him at home, and he spent his last three in a nursing home.

I regularly found myself wishing, or at least, wondering: If only he had died in 2009!

Don’t get me wrong: On my better days, what I was mainly thinking was: If only he had died of a heart attack, his death would have been relatively quick (in theory)… and he would have been spared a near-decade of slowly wasting away – both mentally and physically.

There is space, here, for a discussion of various spiritual perspectives. I’ll leave that complicated topic for a possible, future video. But REALIZE: You can’t control what life gives you; you can only control how you react or respond to it.

Granted, it’s easy to say and hard to do. And I confess: not every thought I had was “altruistic.”

So, number two, we also want to distinguish between a fleeting “bad” thought and an all-consuming idea. Admittedly, there’s a vast middle ground between the two extremes.

Anyone might be susceptible to having the occasional selfish desire. You want to guard against obsessing over such thoughts. For me, this came when my dad was in the nursing home.

Towards the midpoint of dad’s nursing-home stay, we had our first dealings with hospice.

“Hospice” is end-of-life, palliative care for terminally-ill patients. Every time we’d get a call that dad was being “put on hospice,” the news hit us as if he’d just been handed a death sentence. Obviously, I’m speaking loosely. The late-stage Alzheimer’s itself was the real death sentence.

We just didn’t realize that a person can see-saw on and off hospice. Roughly half the time dad was in a nursing home, my family was on edge, expecting that his death might come any day.

That is exhausting, to say the least. Your emotions are like a yo-yo. And it can be both financially and physically demanding.

For example, the first time you think your loved one is at the point of death, you cancel appointments, you take off work, and you otherwise bend over backward to be present as much as possible. If and when they recover, you’re relieved – and not a little surprised, frankly.

But then it happens again. And again. And again. Finally, you worry how you can keep doing this. And you’re basically stuck. If you do react to every wave of hospice as if it were going to be your loved one’s last minutes on earth, then you can place an ever-increasing burden on your family – depending on how many cycles they go through.

After all, it’s not easy to set aside a year, two years, or whatever to be a part of some protracted, open-ended hospice scenario. Sad, but true.

But if you don’t respond, then you risk not being there when your loved one actually passes. You don’t want them to die alone. So, more than once, I wished he would just die. Because I’m here this time. Or my mom is with him right now. Or my sister is visiting from out of town. If he pulls through again, I don’t know which of us will be present next time.

The thing to REALIZE, here, is that we’re only human. The best you can do sometimes, is to take things one day at a time. Have an honest and open dialogue with the hospice and medical staff about your loved one’s situation. And try to plan (as best you can) for rainy-day scenarios.

Regardless of what stage of care you’re in, and where that care is being delivered, try to nip any selfish thoughts in the bud as soon as they pop into your head. Again… easier said than done.

It may help to focus on why you’re doing this. Think about positives – like happy memories. Try to “reframe” the situation, or look at the end-of-life process as a series of opportunities to spend a few more precious moments with your loved one than you thought you’d get.

If you’re in a home-care situation, then consider whether these thoughts – especially if they’re preoccupying you – might be signs of an impending breakdown. Be honest with yourself.

That includes reaching out for help if and when it’s necessary. It might mean that you seek counseling or arrange for respite or hospice care for your loved one.

It doesn’t do any good to simply bury or deny your feelings. The overall caregiving may suffer – which would be bad for your loved one and for you. And that leads to the next consideration.

#8 Regretting Your Caretaking Decisions

It’s an understatement to say it, but …the caretaking road is tiring.

It may also be long and winding. You may feel like you’re wandering lost with no clue how long it will take you to arrive anywhere – or to get back.

You may have mounting debt or expenses. You yourself may be developing age-related physical problems at the same time your loved one is declining. These – and other – factors can lead you to wonder: Can I do this at all? Or …Can I keep doing it?

You can get the distinct impression you’ve bitten off more than you can chew.

And that can lead you to think you made the wrong choice – or a bunch of wrong choices – somewhere along the way. I want to tackle that worry head-on in another video.

But if you start thinking that it was a mistake to take your loved one in, or to assume caregiving responsibilities in the first place, then it can throw you into a spiral of self-doubt.

REALIZE: You’re not alone. Probably every caretaker will harbor similar concerns if they are at it long enough. While this won’t necessarily allay fears that you took a wrong turn, I say it because it’s arguably never clear to anyone what the “correct” path is. You consider your loved one’s well-being of paramount importance, you gather information, you talk your options over with trusted friends and advisers, and you try to do the best you can with the hand you’re dealt.

If, ultimately, things become unmanageable, that may lead to you having to course-correct.

#9 Having to Institutionalize Your Loved One.

And that leads me to this next item. Let me come at this by way of a recent comment. Let’s just say that the opinion was acerbic.

The commenter wrote, in part: “ …I cared for my wife on my own… It did not occur to me to farm her out to await death to make my life more comfortable. …”

Honestly, I doubt that the commenter watched my video. Instead, it seems that he was merely reacting to the title. It’s possible that he misconstrued “When Is It Time for a Nursing Home?” as me saying that – eventually – every caretaking scenario will end with institutionalization. – Which, of course, I don’t believe is true and never said.

Either that, or else he objected that anyone would ever admit their loved one into a nursing home. It’s a view that treats the nursing-home option as tantamount to throwing in the towel (at best) or seeking the easy way out (at worst).

For our purposes, I’m highlighting this because it might easily be taken to heart as an indictment of a caretaker’s commitment to his or her loved one. – As if the only way to show love is to assume full caregiving duties – and stick to them – come hell or high water. Since I turned to professional care, that makes me a bad son.

REALIZE that no one has walked in your shoes. No one should impugn someone’s else’s familial love on the sole basis of their having to utilize a nursing home.

If we didn’t care, we wouldn’t be anguishing over the decision.

But not only is a comment like this uncharitable, it’s really incomprehensible. It half-implies that nursing homes should never be an option.

As many of you know all too well, it’s not always possible – emotionally, financially, physically, or whatever – for family members to be at-home caretakers. In fact, if a better, more complete, kind of care can be delivered in a skilled-nursing facility than in a home, then you could turn the poster’s allegation around and say it would be unloving not to use the nursing home.

Personally, I believe that things are often much more complex and nuanced than either of these dismissive reactions would suggest. For one thing, nursing homes may (or may not) offer quality care. This is just to say that the way forward is not always obvious. In fact, I’d be hard pressed to find a case where the “right decision” is obvious!

No …If there’s certainty in any of this at all, it’s that there is no one-size-fits-all approach.

Thankfully, though, you and I have nothing to prove to anyone else. At the end of the day, it’s for you – in consultation with your support network – to make the best decision you can for your loved one and for your entire family.

#10 Finding That You Don’t Feel Anything at All

Up to now, we’ve been trying to come to terms with various experiences that can make you feel miserable. And that unhappiness can make you wonder if you’re an awful person.

But what happens if you don’t think you’re feeling anything at all?

Someone might hear me explaining how I was tortured over things like the decision to admit my dad into a nursing home or how I was periodically embarrassed by him in public, and so on.

And it’s perfectly imaginable that somebody might think: I’ve never felt anything like that. Does that mean I’m a horrible person?

REALIZE that people deal with adversity differently. I tend to be a reactive, volatile person. I can get worked-up easily.

So, don’t compare – and certainly don’t judge – your emotional reactions to mine or anyone else’s.

But also REALIZE that not feeling anything can mean a lot of different things. For example, it might mean that you’ve become emotionally numb. Caretaker burnout is a real danger.

Remember, also, emotional flatness can be bound up with the so-called “denial stage” of grief processing. So, as I stated earlier, just be willing to be honest with yourself. You might need to take a break. Or you may need professional help – whether for your own mental or physical well-being or for assistance with the day-to-day business of caretaking.

Concluding Remarks

Being a caregiver for someone with dementia can make you feel a lot like Sisyphus. You’ll recall that in the Greek myth, Sisyphus is fated to push a rock uphill for all eternity. Every time he manages to reach the summit, the rock rolls back down the mountain and he has to do it again.

It’s frustrating. It can feel altogether absurd and futile. Additionally, some of the caretaking measures you may need to implement can feel like betrayals. That can be depressing. And it may lead you to feel inadequate, unworthy, and even wretched.

Recently, I realized how many times in past videos I say something like “it sounds bad, but…”.

Why install double-keyed deadbolts on the entry doors? It sounds bad, but… it’s so your loved one can’t easily get out of the house.

How hard is it to care for someone with middle-stage dementia? It sounds bad, but… caretaking can be more manageable if they’re also physically disabled.

I was racked with guilt after having my dad admitted into a care facility. I had nightmares for years afterwards. And it sounds bad, but… the worst were bad dreams in which my dad came back to the house and I was once again thrown into a stomach-churning hopelessness.

You love your afflicted dad, mom, grandparent, spouse, …or child! They’re not actively doing anything to you. They’re not intentionally making you miserable or “oppressing” you.

And you know they’re suffering, too. As my sister said to me during one heart-wrenching exchange in which we discussed institutionalization: Dad is himself in a really bad place.

That’s an understatement, of course.

Trying to imagine what it was like for him is, frankly, sickening. You’re “stuck” inside a body and with a brain that can’t or doesn’t or won’t cooperate with you?! I picture being locked in a windowless room – cut off from others and, eventually, from myself. It’s horrible, hellish, in fact.

Deep down, we know all this “full well,” as the saying goes. That’s the point. The enormity of the pain – on all sides – can be terrifying. Even so, you want so badly to continue to believe that – in their “heart of hearts” – your loved one cares about you, still remembers you, still loves you.

In a sense, it’s precisely that belief – and that hope – that adds insult to injury.

Because… You desperately want to help them. But when they’re cursing you out and throwing things around the house; or when they don’t recognize you and they react to your caretaking as if you were an intruder; or when they refuse to bathe or toilet and you’re routinely cleaning feces off the carpet; you are thoroughly demoralized.

The situation creates an almost impossible tension. You’re sick over the prospect of nursing-home confinement. At the same time, you can feel like you can’t go on and on like this – or you will literally go insane or totally break down physically yourself.

This psychic pressure can build to the point where your mind goes in really dark places.

I’ve been there.

I don’t want to leave this on a negative note.

Please know that I truly, truly, truly empathize.

If you’re presently going through a hard time, then I invite you to share your experiences and thoughts in the comments.

And if you went through a similarly harrowing journey in the past, then I’d ask that you share as well. I have seen really beautiful exchanges in the comments. And I sincerely believe that people who are experiencing self-doubt – or loathing – can benefit from reading about what other people have undergone – and survived.

I hope that – if nothing else – this video encourages you that you’re not alone. And, sometimes, knowing that is about all that keeps you going. I wish you all the best. Thank you for watching.

Comments

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Have you ever considered about including a little bit more than just your articles? I mean, what you say is important and all. But think about if you added some great images or videos to give your posts more, “pop”! Your content is excellent but with images and videos, this blog could definitely be one of the best in its niche. Very good blog!