Insofar as Alzheimer’s Disease erodes the cognitive and mental powers, and insofar as memory is one of these powers, it stands to reason that boosting your memory might serve you well as a dementia-preventive. Let’s go with that! In any case, one interesting and (I think) neglected area in discussions of dementia is memory development.

There are numerous memory-enhancing techniques including the adoption (or construction) of mnemonic devices, the ceasing of over over-reliance upon artificial memory aids, the creation of a so-called “memory palace” (or “mind palace”), and the use of the “major system. Let’s take a brief look at each of these.

Disclaimers

Okay, first of all, I am not a doctor. In fact, I have no medical training whatsoever. So, I am definitely not claiming that memory-boosting techniques are literally a prophylaxis against dementia. There is no scientific research about this either way, as far as I am aware. Rather, the simple and intuitive idea is that forging stronger neural connections and strengthening memory might be an effective – and unexplored – method for stacking the odds in your (and my!) favor. To put it crassly, the better your memory works, the longer it might take to erode.[1]

Second, though, I am by no means an expert on memory, mnemonics, neuroscience, or any similar field. The information and suggestions herein are merely the overflow of my own research. I am interested in avoiding my dad’s end. (If you’re interested in hearing about my personal dealings with Alzheimer’s vis-à-vis my dad, read Jim’s Story, HERE.)

The bottom line, as always, is that my content is presented as-is, with no guarantees or warranties of any kind. It’s just me, chronicling my own investigations and sharing with you, in case you might be interested in picking up where I leave off. (Or, in retracing my steps. Whatever.)

What Put Me onto This? Our Slipping Memories

One day the thought popped into my head that collectively (as a “culture,” whatever that word really means) we might be thought to be suffering from a kind of “mass Alzheimer’s.”

Here’s what I mean. On a daily basis it appears that we use our own brains for fewer and fewer daily tasks.

Generally, we don’t add up our bill at the super market. We let the checker do that. Even if we’re the checker, as a rule, we don’t tally the bill mentally – or even by hand. We rely on a computer to do that.

Now this is just one task. And, admittedly, computers didn’t start this “problem” (if it is a problem). Before smartphones and tablets, we had calculators. I’m not sure if anyone ever carted an abacus around a grocery store. But if they did, then calculators didn’t start the trouble, either.

But what worries me isn’t a grocery bill. It’s the fact that many of us seem to be ceding more and more mental territory over to the machines.

Calendars? Most of mine is on my phone. Phone numbers? How many of those do you actually know by heart?

In other words, it’s conceivable that these electronic assistants are, after all, crutches. It’s possible that they impede our even retard our natural capacities to remember.

The other day I was trying to recollect the name of a movie. In itself, the incident was as meaningless as the piece of information I was trying to recall. But, my first impulse was to just “Google” it.

But I don’t have to remember anything; if Google can remember things “for me”; then… isn’t my own memory starting to atrophy?

Anyway, for what it is worth to you, that was my thinking process. Take it or leave it.

One of my own takeaways is that it’s probably wise to scale back my reliance on artificial memory aids. Instead, I want to make it my goal to try to develop a rich “inner” structure of memory support.

This, in turn, got me enthusiastic for the prospect of revisiting a few memory techniques with which I have been cursorily familiar for several years. I thought that I would just sketch them out – for my benefit (and for that of any interested readers).

A Bit for History Buffs

Many of the tried and true memory systems are certainly not recent inventions. They go back hundreds of years – if not millennia.

The frustrating thing is that a lot of the details have been lost concerning how these systems worked. Here are some notable exceptions.

The 4th-c. B.C. Greek philosopher Aristotle wrote a few passages “On Memory and Reminiscence,” which were included as part of a proto-scientific biological work called a “Brief Treatise on Nature.”[2]

Another important early text is titled, in Latin, Rhetorica ad Herennium (circa 80-90 B.C.). This opaque phrase simply refers to the fact that it is a treatise on rhetoric written specifically for a now-unknown person named “Herrenius.” (Read some of the relevant passages, translated in English, online HERE. It’s only about fifteen paragraphs in the English translation.)

If it weren’t for the spectacular stories told to illustrate the prodigious feats of memory that were supposedly possible based on ancient memory techniques, these scattered writing might be considered nothing more than curious historical footnotes. But consider the case of one Simonides of Ceos.

According to the tale, Simonides was invited to a great feast at which there were dozens of other attendees. (Unfortunately for this article on the power of memory, I have forgotten the exact number of other guests – which is probably unknown in any case.) Let’s say that there were 100 people present.

At some point during the feast, Simonides was summoned out of the dining hall. No sooner had he left than the building collapsed with a great crash. Not only were the occupants killed, they were mangled beyond all recognition.

Bystanders, investigators, and would-be rescuers fretted over the seemingly futile task of identifying the victims. But, so the story continues, Simonides was able to recall each guest and his or her place at the great feasting tables. He did this through a fantastic mastery of the “method of places” (or loci), which was one facet of the memory skills that have faded into obscurity.

Going on, the famous Roman statesman and philosopher Cicero wrote about some memory techniques in a book called “On the Orator.”[3] We also have a few comments from the rhetorician Quintilian in his “Institutes of Public Speaking.”[4]

Truthfully, however, most of these works consist of little more than roundabout references to the Ars memoriæ (the “Art of Memory”). None of these surviving works is anything like a thoroughgoing teaching manual. The references mostly assume that readers are fully familiar with the methods under discussion.

This means that interested persons today need to do a bit of sleuthing – and depend upon the reconstructions of various scholars.

However, these investigators do have a bit of secondary literature to go on.

For example, such techniques (or something similar) were apparently known to the Medievals. Well-known Catholics like Albert the Great and his protégé, Thomas Aquinas, incorporated memory methods into their approach to learning and theology, a blend that has come to be termed scholasticism.

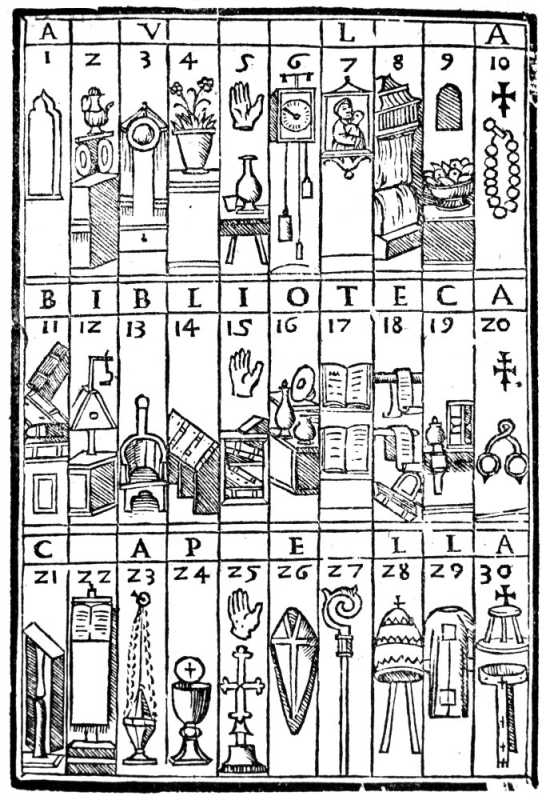

Or again, the relevant ancient memory techniques were apparently resurrected around the 16th century, during the Renaissance, by such authors as Johannes Romberch[5] and Giordano Bruno.[6] Memory feats were again taken to high, Simonides-like levels by people like the aforementioned Bruno, as well as thinkers such as Athanasius Kircher and Matteo Ricci (among others).

In the 17th century, an obscure English writer named Henry Herdson published a few short texts on the subject, the most important of which was Ars Memoriæ: The Art of Memory Made Plaine (sic).[7]

Closer to our time, the late 20th-c. British historian Frances Amelia Yates examined and then repackaged a lot of the available information in her important The Art of Memory.[8]

Within two years of the publication of Yate’s research, the important 20th-century neuropsychologist Alexander Luria wrote up his case study on Solomon Shereshevsky, a supposedly untutored Russian businessman who had an intuitive mastery of various “imaginal” memory strategies.[9]

Shereshevsky was an exceptional and intriguing figure. But as far as can be determined, it wasn’t as if he had been privy to some ancient learning that is unavailable to the rest of us. He just seemed to devise various memorization strategies himself and was able to implement them with an uncanny ease.

More recently, some of these ancient techniques – or our modern approximations – have been the subject of a best-selling book, Moonwalking With Einstein, by New England-based journalist Joshua Foer.[10]

What Are the Actual Techniques?

If you read the foregoing – and didn’t just skip down – you might be saying: “That’s all well and good. But what is really going on?”

And, more practically speaking, how can a person boost his or her memory? In other posts, I give recommendations for how various herbs, nutrients, physical exercises, and vitamins can help to enhance and support brain functions. (Check those out HERE, HERE, HERE, HERE, and HERE.)

But there are additional mental activities and exercises that can augment – or at least “work out” – our innate abilities to store and recall pieces of information. Here are some of those techniques – briefly summarized – along with a few additional tips.[11]

Don’t (over-)rely on memory aids.

This is the first and, given what I wrote earlier, possibly the most obvious. If our memories are being deteriorated by underuse, then the most apparent starting place will simply be to start using it. You don’t need to move straight into memorizing a list of 100 guests at a dinner party. Start with the ten items that you need to grab from the market or the phone number for the doctor’s office.

Use the ‘major system.’

But you have trouble remembering numbers, you say? Well, never fear, for there are one or two “tricks” up a mnemonist’s sleeves. The “Major System” is a sort of phonetic numbering tactic. The system entails letting letters stand in for numerals. The idea is that if you can turn numbers into words, you can recall them more readily.

There are several variants floating around, but the one that I was exposed to goes like this.

- 0 stands in for “S,” “TS,” “Z”

- 1 stand in for “D” and “T”

- 2 stands in for “N”

- 3 stands in for “M”

- 4 stands in for “R”

- 5 stands in for “L”

- 6 stands in for “CH,” “G” (soft), “J,” and “SH”

- 7 stands in for “G” (hard) or “K”

- 8 stands in for “F” and “V”

- 9 stands in for “B” and “P”

Consider a number, like 555-1212. Suppose that someone gives you this as the name of an Alzheimer’s specialist that you should contact. The idea of the major system is that you can bring in your letter substitutions. So the “5s” would become “Ls”: 555 = LLL. Then the “1212” becomes either: “DNDN” or “TNTN” (or some variation: such as “DNTN” or “TNDN”).

You then create a memorable word or phrase by inserting vowels in between the consonant letters. So, “LLL” might become “aLLeLuia” and “TNTN” might become “TiNTiN.” And you might imagine the Belgian cartoonist’s Tintin character exclaiming “Alleluia!” or singing Handel’s famed chorus.[12]

Create Mnemonics for Yourself

The word “mnemonic” has come to mean, basically, memory aid. It comes to us from the Greek word “mnemonikos[,] ‘of or pertaining to memory’.”[13]

Of course, this method is as varied as it is tried and true. What school child hasn’t had the experience of learning the names of the Great Lakes by memorizing the acronym “HOMES” – representing Lakes Huron, Ontario, Michigan, Eerie, and Superior?

The lesson? You can give your memory an assist by linking longer lists to something shorter and more readily remembered. So, the lakes might be harder to recall by themselves. But when we “hook” each of their names to a letter in a word like “homes,” we give ourselves a kind of memory “handle.”

There is another way that this can be made to work for you. To get at it, consider something called the “Baker-baker Paradox.”

Simply stated: “Remembering that a man’s name is Baker is harder than remembering that he is a baker. [Oxford-based experimental psychologist] Gillian Cohen called this the ‘Baker-baker paradox.’ The exact same word, ‘baker,’ is hard to remember as a name, but easy to remember as a profession.”[14]

As author Joshua Foer put it in his “TED Talk,”[15] the key to mining memory-boosting tips from this psychological principle is as simple as “turning big ‘B’ Bakers into little ‘b’ bakers.”[16]

Foer illustrates this by suggesting that if you have to remember that someone’s last name is “Baker,” you can improve your chances of doing so by picturing the person decked out in the accoutrements of the baking profession – baker’s hat, rolling pin, bags of flour, etc.

I was once introduced to a somewhat stout bank teller by the name of “Joe.” With no disrespect, I immediately thought of “sloppy Joe” and visualized him wearing a messy apron. Months later when I had the occasion to return to that branch (which was otherwise off the beaten path for me), I saw his face, which triggered the image, and I was able to greet him by name – which surprised him , frankly.

Build yourself a mind palace.

The importance of this technique is matched only by its complexity and nuance. The previously mentioned Giordano Bruno (among others) spent an entire book teasing out some of the subtleties. In this small space I can only scratch the surface.

The basic idea is the combination of mnemonic devices and the creation of a mental construct variously called a “memory palace” or a “mind palace.”

Fans of British television may already possess a passing familiarity with this method, as it features in the BBC’s Sherlock, with Benedict Cumberbatch playing the timeless Sherlock Holmes and Martin Freeman ready at hand as his trusty friend and partner, Dr. John Watson. Additionally, mind palaces assume great importance in shows involving the self-proclaimed “psychological mentalist” Derren Brown.[17]

The mind palace works roughly like this. First you visualize a sprawling space. I think that the idea is to conceptualize a location with which you are intimately familiar. So, you might use your house, for example. Let’s say that you do.

Next, you take a list of things that you need to remember, and you make the list more readily memorizable by “coding” the objects, names, or numbers (or whatever it is you need to remember) into vivid mental pictures. You then “place” these images around your well-known location.[18]

Now, I am no expert on this, but my impression is that you would do something like the following. Suppose you have to purchase butter, eggs, potatoes, milk, and flour from the grocery store. You imagine a cow holding a bouquet of flowers to encode the “milk and flour.” Perhaps you mentally position this cow in the entryway of your house. You proceed into the interior or the home, let’s say ending up the living room. And you picture a flaming potato in your fireplace. Walking a little farther, you glance into the kitchen. Maybe you code the “eggs and butter” by picturing a chicken sliding around on butter smeared on the tiled floor.

What you end up with is your list of five grocery items, transformed into memorable images, and strewn around your house in a particular order.

The utility of the loud and crazy images is that they make recall easier than it would be if you were trying to remember the boring objects by themselves. And the point of placing them around a physical location is to keep track of what you have to remember. By mentally “walking through” your image of the house, you will “notice” the objects deposited in various places. You won’t forget anything, according to adherents of this method, because you will encounter each item as you proceed through the space. This is why the space ought to be a familiar one – like your own home.

Summary

4 Quick Memory-Boosting Tactics

- Try not to rely on calculators, smartphones, or Google. Use your own brain!

- Convert numerals into words with the “Major System.”

- Transform lists into words and Bakers into bakers (see above!) with mnemonics.

- Construct a “memory palace” and place items inside of it using the “method of places.”

For the details, refer to the main text. Happy remembering!

Further Reading

“10 Things to Do Now to Reduce Your Alzheimer’s Risk Later in Life”

“How Does a Person Actually Die From Alzheimer’s Disease?”

“75+ Questions to Ask a Doctor About an Alzheimer’s Diagnosis”

Notes:

[1] Is this true? I don’t know. But it sounds plausible to me. And, frankly, using these techniques has a number of ancillary benefits, anyway. I suppose what I’m saying is that there’s little to no downside to this – unless, of course, you don’t want to invest the time. Which is a totally fair point, and completely up to you.

[2] In Greek, Peri Psuchēs: Peri Mnēmēs kai Anamnēseōs; in Latin Parva Naturalia: De Memoria et Reminiscentia.

[3] De Oratore, 55 B.C.

[4] Institutio Oratoria (12 vols.), circa A.D. 95.

[5] See his Congestorium artificiose memoriæ (roughly translated as “Tales Concerning the Kinds of Memory”), Venice: M. Sessa, 1520; 1533.

[6] See De umbris idearum (“On the Shadows of Ideas”), Paris: Ægidium Gorbinum, 1582; Ars Memoriæ (“The Art of Memory”), Paris: Ægidium Gillium, 1582; and Cantus Circæus (“Circe’s Song”), Paris: Ægidium Gillium, 1582.

[7] Henry Herdson, Ars Memoriæ: The Art of Memory Made Plaine, London: Gartrude Dawson, 1651.

[8] Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1966.

[9] See Alexander Luria, The Mind of a Mnemonist: A Little Book About a Vast Memory, New York: Basic Books, 1968.

[10] Joshua Foer, Moonwalking with Einstein: The Art and Science of Remembering Everything, New York: Penguin, 2011.

[11] I just concluded a section enumerating many scholarly tomes unpacking the Art of Memory

[12] I realize that it’s normally referred to as the “Hallelujah Chorus,” but this is arguably just a transliteration quibble and, well… you get the picture.

[13] Douglas Harper, “Mnemonic,” Online Etymology Dictionary, 2018, <https://www.etymonline.com/word/mnemonic>.

[14] Ira Hyman, “Large Mocha without a Name,” “Mental Mishaps” (blog), Psychology Today, Feb 24, 2010, <https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/mental-mishaps/201002/large-mocha-without-name>.

[15] Joshua Foer, “Feats of Memory Anyone Can Do,” YouTube, May 10, 2012, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U6PoUg7jXsA>.

[16] Ibid.

[17] For an entertaining illustration of which, see HERE.

[18] This is also sometimes called the “method of places.”