Alzheimer’s is a degenerative brain disease that causes diminution of cognitive abilities, including memory, perception, and reasoning. As of this writing, Alzheimer’s Disease afflicts between 5.5 and 5.8 million people in the United States and between 44 and 47 million people in the world. It’s possible causes – discussed HERE – are not well understood. (There are widely mentioned RISK FACTORS.)

Various researchers, however, have suspected that at least some of the blame for Alzheimer’s can be placed on controllable things like diet/nutrition and exercise – both mental and physical. The general idea is that if you don’t “use it” (i.e., your brain), you might “lose it”![1] To that end, several sources have posited a slew of activities that are geared toward keeping you cerebrally fit. I’’ take a sort of “cocktail” or “grab-bag” approach.

Here is my list of the top twelve ways you might be able exercise your brain to prevent Alzheimer’s Disease. (See “Caveats,” below.)

Board and Card Games

An article in the British newspaper Independent related that “playing board games …could help” with mental decline – perhaps to an even greater extent than working crossword puzzles (about which, more in a moment).[2]

According to the results of one study that looked at brain scans: “Middle-aged people who [are] avid game players …[tend] to have bigger brains than people who [do] not play games…”.[3]

These more massive brains can confer a big advantage. Some people refer to this as “cognitive reserve.”[4]

Brain Teasers

“Brain teasers” are a type of game, usually consisting of problems, riddles, and the like of that that are solved usually for amusement. But what if they could serve a more useful purpose?

Numerous news outlets have reported on the possibility that various brain teasers, mathematics puzzles, and mysteries might help to enhance your cognitive health.

In the article “How to Outsmart Alzheimer’s,” Wall Street Journal columnist Amy Marcus reported that “quizzes and other cognitive challenges” might push back the onset of Alzheimer’s – “perhaps indefinitely.”[5]

So, reach for those puzzles and put your mind to work!

Chess

Chess is a two-player strategy game that has been around for hundreds of years. It’s played on a board composed of 64 squares of alternating colors. In total, there are 16 pieces per side (32 in all): eight pawns, 2 knights, 2 bishops, 2 rooks, 1 queen, and 1 king. Each type of piece has different rules governing its legal moves. The overall objective of the game is to “corner” (or “checkmate”) the opponent’s king in such a way as to leave it with no counterattack or means of escape.

Chess can be a very involved game with lots of subtlety and variety. It has competitive and social aspects (on the further benefit of which, see further on). But, on the other hand, it can be played over the internet without you (or your loved one) having to leave home.

Once again, some researchers suggest that “playing chess helps stave off the development of dementia.”[6] In fact, one study showed that playing chess “resulted in an almost 30% reduction in” dementia risk.[7]

Checkers

A two-player game, checkers is similar in some respects to the aforementioned chess. For instance, the board consists of 64 alternately colored – or “checkered” – squares.

Checkers is, however, played with 12 pieces per side instead of 16. Each piece is the same at the beginning of the game: simply a small, circular disk. The object of checkers is to “capture” or remove all (or at least most) of your opponent’s pieces or to leave him or her without any legal moves.

Although checkers has less variety in terms of pieces and moves, it is plenty rich in terms of move combinations and traps.

“Studies show games like checkers can boost your brain strength.”[8]

Crosswords

Admit it: Here’s the one you’ve probably been waiting for!

Simply put, a “crossword” is a kind of word puzzle. It is usually presented as a sort of grid with a combination of “empty” boxes and shaded boxes. The object of a crossword is to answer questions or use clues to fill in the empty boxes with words. Often, the words crisscross and interconnect in interesting ways – usually by sharing letters – which accounts for the name of this puzzle type.

Some investigations have suggested that working crosswords can boost mental ability and function.

Whether these activities affect age- or Alzheimer’s-related cognitive decline is an open question.

However, the National Center for Biotechnology Information, part of the National Institute of Health, published a study revealing that doing crossword puzzles delayed cognitive impairment – specifically, memory decline – by an average of two and a half years.[9]

Language

There’s a joke that goes something like this.

Question: What do you call a person who speaks three languages? Answer: Trilingual. Question: What do you call a person who speaks two languages? Answer: Bilingual. Question: What do you can a person who speaks only one language? Answer: American!

A quick Google search suggests that around 80-85% of Americans are monolingual.[10] Similar percentages apply in Canada. And the United States and Canada have some of the highest rates of Alzheimer’s Disease. For instance, it is the sixth leading cause of death in this country.

This is compared to approximately 45% of Europeans who are monolingual.[11]

Some research suggests that being bilingual can delay the onset of dementia.[12] For example, a 2013 article from CBS News is titled “Learning Another Language May Help Delay Dementia.”[13]

The article reported on a scientific study of various subpopulations in India. The suggestion was that speaking another language can push Alzheimer’s onset back an average of four to six years.

However, a key word is delay. Many people Belgium and Iceland are multilingual. However, both of those countries are in the top ten of nations with high percentages of Alzheimer’s dementia – according to WorldAtlas.com

In fact, Finland is the nation with the highest affliction rate. And a preponderance of the population appears to be bilingual to one degree or other.

Still, it seems reasonable to talk about a “protective effect of bilingualism.”[14]

Music

I have written a bit about how musical therapy can be a helpful intervention to explore when it comes to treating Alzheimer’s sufferers. (See my article “Can Music Calm an Alzheimer’s Patient?”)

A few studies have also led investigators to conclude that things like “playing musical instruments” can be better than working crossword puzzles or doing Sudoku. In fact, some suggest that this can “significantly reduce” a person’s risk.[15]

But for a more complete look at risk factors, see my video dedicated to that topic.

Puzzles

For those who weren’t introduced to these as children, jigsaw puzzles are basically jumbles of irregularly cut pieces (originally of wood, but now largely cardboard or plastic) that must be assembled in the correct order to reveal a pattern or picture. Pieces range in size from large (for small children or Alzheimer’s sufferers) to small (for people of normal to high cognitive function who may be looking for a challenge).

This deep into the article, you can probably predict what I’ll say next. “[J]igsaw puzzles …can help keep the mind active and a little sharper.”[16] (There are numerous kinds available. For my suggestions, see HERE.)

Reading

Some researchers believe that simply reading (books, magazines, etc.) frequently can have a protective and supportive effect on our brains. This could honestly be as mundane as picking up the daily newspaper. Or, for people who are more electronically inclined, visiting your favorite news website.[17]

If you walk to your local library, you could add a bit of exercise into the mix as well!

Social Interaction

According to a report from National Public Radio: “social interaction may be a better form of mental exercise than brain training,” where “brain training” refers to exercises designed to enhance processing speed and promote reasoning.[18]

Just “being around” other people can be of great benefit to Alzheimer’s sufferers.

Still, it is well to recall that causal direction is difficult to establish. Is it that social withdrawal leads to Alzheimer’s, or that Alzheimer’s leads to social withdrawal?

Sudoku

Here’s another – and more arithmetical – sort of puzzle: Sudoku. This Europe-originated puzzle with the Japanese name is essentially a reworked “magic square” in which numbers are inserted into a 9×9 grid. The object of the number game is to fill paper so that every column, row, and embedded 3×3 grid contains all numerals from 1 to 9.

One scientist stated: “…doing Sudoku isn’t probably going …to prevent you from developing Alzheimer’s disease” by itself.[19] Still, there’s little doubt from many investigators that “regular use of word and number puzzles” – like Sudoku – “helps keep our brains working better for longer.”[20] At least one scientific “study has identified a close relationship between frequency of number‐puzzle use and the quality of cognitive function in adults aged 50 to 93 years old.”[21]

If numbers are in your wheelhouse, give it a shot. If letters are more your thing, feel free to see our section on “crosswords,” above!

Working

You read that correctly. We’re talking about going to work.

Before you complain about your job, consider that, for many people, their job provides their “daily cognitive training.”[22]

This is to say that just going to work can have some neural-protective value.

Many jobs are going to present workers with daily brain challenges. These may include having data to enter, information to process, items to remember, things to multi-task, questions to answers, and so on.[23]

Now, if your nine-to-five has you on the verge of a panic-induced coronary, then you might want to seek stimulation elsewhere. But if your day job isn’t overly stressful or soul-sucking, then realize that it might be giving your brain an assist.

Caveats

When it comes to Alzheimer’s prevention, there are three divergent perspectives on the efficacy of mental exercise. These are as follows. (1) Mental exercise is possibly helpful. (2) Mental exercise is likely neither helpful not harmful. (3) Mental exercise is potentially harmful.

Objections

The third position – that mental can be potentially harmful – suggests a few objections to the strategies outlined above.

False Hope?

Firstly, some investigators worry that these considerations might give a person “false hope.” The idea, here, is – presumably – that someone might form beliefs such as that doing crossword puzzles has the power to confer some sort of magical protection against dementia, or that doing them could even reverse the disease. Sadly, these don’t seem to be the case.

But it seems to me that the solution is to have realistic expectations, rather than abandoning the idea of doing mental exercises.

Ineffective?

Secondly, and relatedly, some people object that these interventions are just plain ineffective. For example, in some studies – like regarding bilingualism – participants ended up getting Alzheimer’s anyway.

But this shouldn’t mean that the interventions are without value. It may be that we have to clarify what we mean by “effective.” If “effective” has to mean 100% protection against Alzheimer’s, then we might have to confess these interventions to be “ineffective.” But could mental exercises be “effective” at delaying Alzheimer’s?

Delaying onset of a disease seems valuable in and of itself. For example, if you can maintain a higher quality of life longer, wouldn’t you want to do it?

So, maybe playing checkers or working won’t guarantee that I never get Alzheimer’s. But if they (and other things) can help me to push onset back 2 years, 4 years, 6 years… it’s worth it to me.[24]

However, some people mention another facet of this objection. To put it directly, it’s possible that “incipient” or as-of-yet undetected dementia might prompt people to withdraw from social situations and to cease engaging in mentally stimulating activities.

On this picture, it’s not so much that you should exercise your brain to ward off Alzheimer’s. It’s more that once you reduce your level of mental engagement, it’s likely that you have Alzheimer’s – latently – already.

Of course, it is true that I don’t have any special insight into the mechanics or direction of the causation – if any – between mental exercise and dementia. It could be that dementia causes a lack of mental exercise; it could be that a lack of brain engagement causes dementia; it could be that they both have a third, presently unknown cause; or it could be that they are causally unrelated.

Still… only one of those possibilities suggests any direct way for me to influence my mental health positively. In the absence of some impelling reason for me to think that brain exercise isn’t at least possibly beneficial to me, I’ll continue to operate as though it might.

Counterproductive?

Thirdly, some commentators have spoken (or written) in such a way as to suggest that brain exercises could actually be harmful! A few titles make statements such as that mental training can “speed up dementia.” A few acknowledge that mental stimulation might buy time, but that it also accelerates decline once it begins.

There are a few things to be said.

Number one, insofar as these statements make it seem as if someone could be worse off for having exercised their brains, these summaries are a bit misleading. The “acceleration” of the decline can be explained as a simple matter of mathematics, provided only that the dementia is at least partially a matter of biology or physiology.

What I mean is this. Mental exercises almost certainly help boost or preserve cognitive function. But Alzheimer’s involves literal, physical damage to the brain. So, ultimately, mental exercises cannot undo physical damage.

However, through things such as by increasing “cognitive reserve,” they may be able to stave off the noticeable effects of the condition. But this means that once the effects of the condition do become noticeable, the disease may be “compressed,” and the decline may appear to be more rapid or steeper than it would have been otherwise.

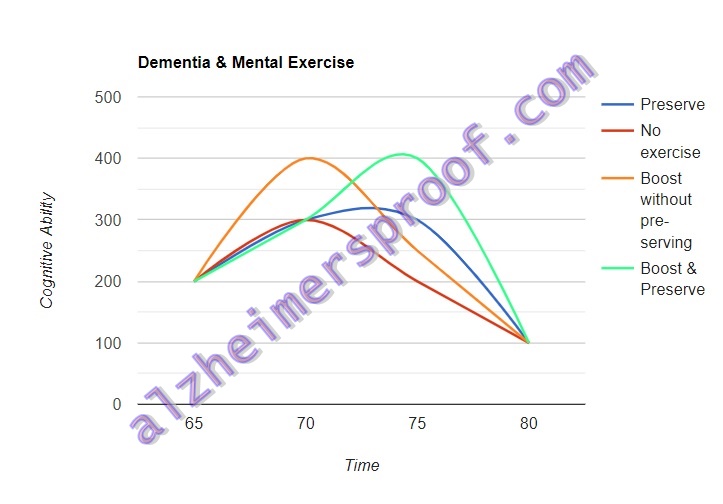

Mathematically, this means that the decline is “quicker” either in that it happens over a shorter time, or that it occurs from a higher “starting point” – or both. This can be seen fairly readily from a simple curved-line graph.

In the graph, I show four different trajectories, all ending at age 80.

Red line: no exercise

The red line represents a person who doesn’t exercise at all, and whose decline begins at age 70. The decline concludes at age 80 – as it will for each of the four imagined scenarios.

Blue line: exercise preserves brain function

The blue line represents a person whose exercise preserves their cognitive function an extra five years. So, their decline begins at age 75. It still concludes at age 80.

Orange line: exercise increases, but doesn’t preserve

The orange line represents a person for whom exercise gives their brain function a boost. I didn’t also assume that this boost bought them any additional time. So, you see their decline begins at the same point as the person who doesn’t exercise at all: age 70. This is the person who has a “higher starting point.” The decline also ends at age 80.

Green line: exercise increased brain function

Finally, the green line represents the person for whom exercise both gives a boost to brain function and preserves it. Obviously, this is the best-case scenario. Since the brain function is boosted, the starting point is higher. Since it is preserved, I have their decline begin at age 75. Like everyone else, it stops at age 80.

Analysis

In this toy model, I have envisioned four scenarios, representing four possible combinations. (1) No boost to brain function and no preservation of brain function;[25] (2) preservation of brain function with no boost; (3) no preservation of function, but some boost; and (4) both preservation and boost.

In each of the four cases, we’re looking at people between the ages of 65 and 80. I have assigned arbitrary “brain-function points” between 100 and 400.[26] Furthermore, I have supposed that people start to decline beginning at age 70 or 75, depending on whether there is preservation or not.[27]

(You could either see these as representing four different, but relevantly similar, people. Or you could see it as representing four different possible trajectories for one and the same person. I prefer the latter.)

The four resulting combinations are as follows.

No boost, no preservation

The red line depicts a person who doesn’t engage in any mental exercise at all. The decline begins at level “300” (just an arbitrary number) and ends at level “100.” This is a difference of 200 points. It takes ten years, which means that they lose twenty points a year.

No boost, preservation

The blue line buys the person an extra five years of preservation. Since they hit the same level – level “100” – at the end, their decline occurs twice as fast as for the person who didn’t exercise. They drop 40 points per year, which is twice the rate of decline. This is because the same amount of decline (as occurred with red) is compressed into half the time.

Boost, no preservation

The orange line shows a person with a bit of a boost (getting them to 400), but no extra time before decline begins. They start higher, but end in the same place, dropping 300 points in ten years. This yields a rate of 30 points per year. The amount of decline (compared with red) is 1.5 times greater (150%) but is stretched over the same length of time (as red).

Boost, preservation

The green line shows a person with both boost and preservation. This person bought an extra five years before visible decline. But they also have the extra “100 points” of function. So, their decline starts at a later age (compared to red) – age 75 – and from a higher starting point (again, compared with red) – 400 points. Since they decline 300 points over five years, their rate of decline is 60 points per year.

Conclusion

That we see “higher rates” of decline in the exercisers is due to either (or both) of two factors.

Factor 1: The decline happens over a shorter span of time (as with blue and green); or…

Factor 2: The decline happens from a higher starting point (as with orange and green).

I said earlier that the explanation for the higher decline rates was mathematical. When a predetermined amount of decline happens over a shorter time frame, the rate of decline is increased. This is mathematical in this sense. Take some number, n. n divided by 5 is going to be bigger than n divided by 10.

Moreover, when a predetermined endpoint of decline is reached from a higher beginning point, the slope of the line representing that decline is steeper.[28] This is also mathematical, since the slope of a line is merely a value (m) in the equation representing that line. So, if the cognitive “drop off” is steeper, all we’re saying is that the value of slope (m) for that drop off is a bigger number than it is if the drop off were not as steep.

At the end of the day, for me, I would rather have my cognitive function preserved for as long as possible – and boosted as high as possible – even if I experience an eventual decline.[29]

Curiously, you could even argue that having a “quicker” or “higher” rate of decline is preferable to a slower rate in that it likely saves caretaker energy as well as money devoted to care!

Training Is Parochial

Fourthly, you may read that certain forms of “brain training” are very limited in terms of what they accomplish. Even where certain mental exercises may be worthwhile, their impact may be restricted. To put it another way, specific benefits may not generalize to other areas of your daily or mental life.

For example, reading books may help boost your processing speed, but maybe doesn’t help enhance your memory. (It’s just an illustration; I don’t know whether it does or doesn’t.)

Somewhere I read a researcher giving the following analogy. Some brain exercises can be likened to working out physically by doing only one or two exercises. These exercises – like bicep curls – may strengthen a single muscle (the biceps), but they are unlikely to impact the overall health of the body much.

A few things may be said in reply. Number one, you can make the case that doing a few exercises is better than doing none. A person who does biceps curls may not be as fit or healthy as a person who trains his or her whole body. But he or she may well be more fit or healthy than he or she would be if they did nothing at all.

Number two, whether a given exercise has broad or narrow impact may depend on the sort of exercise being done. In physical training, there are differences between compound and isolation exercises. It’s one thing to do bicep curls or grip strengtheners all day long. It’s another to do deadlifts or squats. The former may only affect one or two muscles; the latter might well affect the entire body. It is doubtful that we know enough about “brain training” to really understand the broader impact of a lot of the mental exercises discussed here. For example, is playing chess more than doing bicep curls, or more like doing squats? I’m not sure. And I’m not sure that anyone else is sure, either!

Blame the Victim?

Yet another objection, fifthly, is that talking about mental exercise may lead to sufferers being “blamed” for their Alzheimer’s. The idea here is that some people might conclude that if John Doe has dementia, then he must have been mentally inactive or lazy.

Sometimes you may read comparisons to smoking. People who smoke are at higher risk of lung cancer. So, if a smoker gets lung cancer, then he or she assumes some of the responsibility for that condition.

By way of response, I should first remind readers that Alzheimer’s risk almost certainly has a – probably a significant – genetic component. (See my video about risk factors HERE; or read the article on the same topic HERE.) To put it differently, some people are simply more at risk than others of developing it.

Having said that, I will simply repeat what I have mentioned many times in my written and video-graphic work: I am trying to stack the odds in my favor. I realize that if I smoke, I’ll be at increased risk for lung cancer. Although the data may not be as clear cut for the relationship between mental exercise and dementia, I’ll say that for me personally I’d rather exercise, and have it avail me nothing, than not exercise and have it turn out that it would have helped me.

If other people value other things over exercising, then I would suggest that it is their prerogative to do so. In the first place, the data in favor of mental exercise is not so compelling as to make it undeniable that it helps preserve or boost cognitive function or that it can ward off Alzheimer’s.

But even if the data were that compelling, it’s not clear that someone has to value preserving or boosting cognitive function or must value warding off Alzheimer’s, over not doing any of these. I confess that such a position would be foreign to my own thinking. But it’s not something that moves me to start throwing words like “blame” around.

I suppose you could put my answer this way. If a person doesn’t perform mental exercises, it’s either because they don’t think it will help or they don’t care if it helps or not. If they don’t think it will help, then their choice not to exercise is rational. They have discharged their rational duty and it’s not obvious to me that there’s anything to blame them for.

If they don’t care, then the choice itself may be irrational (i.e., not rational). But it’s not clear why a person choosing irrationally in this way wouldn’t care if exercising helps but would care if they’re “blamed” for not caring. It seems to me more likely (or at least more consistent) if they didn’t care about either one. So, even if the choice is blameworthy, it doesn’t appear to have the result the objector is worried about. It seems that the concern in the objection is centered on the perceived hurt feelings of the person being blamed. But, to reiterate: for all we know, the person who doesn’t care about not exercising wouldn’t care about being blamed for not exercising. If this is so, then it’s not obvious that there would be any hurt feelings for us to worry about.

Conclusions (Tentative)

One article ventured the opinion “that lifestyle choices may even counteract genetic predisposition for Alzheimer’s.” If true, that’s huge.[30] And it would put a lot of control in our hands.

Here are a few takeaways.

Train the Whole Brain

But staying mentally fit and sharp may really come down to neural recruitment: using multiple parts of your brain, not just a few.

Be Consistent

It’s also going to involve consistency. Many reports mention the need to engage in stimulating activities regularly – say two or more times weekly – not just every blue moon.

Try Something New

Another key element is novelty. Sometimes trying something new may be more valuable than doing the same things over and over. There may be two “levels” of novelty. Think about some of the things on this list. For example, chess or reading. Every game of chess you play has the possibility of being different from every other game. And if you read new articles or books every day, you are adding some variety. However, we might call this low-level variety. A higher level of variety can be attained if you learn a new language or musical instrument, for example. Interestingly, there may be a kind of middle level as well. For example, a person could switch from reading fiction to nonfiction, or from reading prose to reading poetry.

Act as Though It’s ‘Use It Or Lose It’

As the Independent put it: “use it or lose it” idea may just “give a person a ‘higher starting point’ from which to decline.” But this still seems advantageous.

Realize: ‘Better Late Than Never’

Some commentators express the message that its always “better late than never.” But you should probably take the position that it’s desirable to start now! This applies to you whether you are a sufferer or a person looking to avoid the condition altogether.

No Silver Bullets

Still, neither I nor most other researchers are suggesting that any of these measures amounts to a “cure.”

Aim to Have a Healthy Lifestyle

Additionally, these mental activities almost certainly need to be situated in a larger context – a “lifestyle package,” as it were. Genetic predisposition notwithstanding, if you really want to stack the odds in your favor, you’ll need to address your blood pressure, body mass, cholesterol, diet, level of physical exercise, and sleep patterns.

I can tell you that I’m implementing a number of these measures today. Most of the items on this list are cheap (or free) and easy to obtain. And after all that’s been said, I think it’s reasonable to maintain that they can’t hurt. And some of them just might help. So…go on: give your brain a good workout!

[1] See, e.g., Chiara Giordano, “Doing Sudoku and Crosswords Won’t Stop Dementia or Mental Decline, Study Suggests,” Dec. 11, 2018, <https://www.independent.co.uk/news/health/sudoku-crosswords-dementia-mental-decline-brain-study-aberdeen-university-research-a8677466.html>.

[2] Giordano, loc. cit.

[3] Felix Gussone, “5 Things You Didn’t Know About Alzheimer’s,” CNN, Jul. 17, 2014, <https://www.cnn.com/2014/07/14/health/alzheimers-disease-conference/index.html>.

[4] See, e.g., Margaret Gatz, Educating the Brain to Avoid Dementia: Can Mental Exercise Prevent Alzheimer Disease?” Public Library of Science, vol. 2, no. 1, Jan. 25, 2005, p. e7, <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC545200/>.

[5] Amy Marcus, “How to Outsmart Alzheimer’s,” Wall Street Journal, Mar. 30, 2010, <https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052748703416204575145921517534304>.

[6] Allison Aubrey, “Mental Stimulation Postpones, Then Speeds Dementia,” National Public Radio, Weekend Ed. Saturday, Sept. 4, 2010, <https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=129628082>.

[7] Ivan Vega, “‘Checkmate the Onset of Dementia’: Prescribing Chess to Elderly People as a Primary Prevention of Dementia,” Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, Jan. 25, 2019, <https://www.j-alz.com/editors-blog/posts/checkmate-onset-dementia>.

[8] Gussone, loc. cit.

[9] According to Jagan Pillai, Charles Hall, Dennis Dickson, Herman Buschke, Richard Lipton, and Joe Verghese, “Association of Crossword Puzzle Participation with Memory Decline in Persons Who Develop Dementia,” Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, vol. 17, no. 6, Nov., 2011, <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3885259/>.

[10] At least, this is the assertion of the weblog Puerto Rico Report, in the post “Bilingual America,” Aug. 11, 2017, <https://www.puertoricoreport.com/bilingual-america>.

[11] Ingrid Piller, “Multilingual Europe,” Language on the Move, Jul. 18, 2012, <https://www.languageonthemove.com/multilingual-europe/>.

[12] The precise time of onset can be extremely difficult to identify.

[13] Ryan Jaslow, “Learning Another language May Help Delay Dementia,” CBS, Nov. 6, 2013, <https://www.cbsnews.com/news/learning-another-language-may-help-delay-dementia/>.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Giordano, loc. cit.

[16] Rob Nelson, “Hidden Heroes: Queens 12-Year-Old Helping People With Alzheimer’s,” ABC News, Apr. 26, 2019, <https://abc7ny.com/health/hidden-heroes-queens-12-year-old-helps-people-with-alzheimers/5272644/>.

[17] Though, for the counterpoint that online reading may be detrimental, see “‘The Shallows’: This Is Your Brain Online,” National Public Radio, All Things Considered, Jun. 2, 2010, <https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=127370598>.

[18] “A Brain Scientist Who Studies Alzheimer’s Explains How She Stays Mentally Fit,” National Public Radio, Morning Ed., Oct. 8, 2018, <https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2018/10/08/654903558/a-brain-scientist-who-studies-alzheimers-explains-how-she-stays-mentally-fit>.

[19] “A Brain Scientist Who Studies Alzheimer’s Explains How She Stays Mentally Fit,” loc. cit.

[20] “Sudoku or Crosswords May Help Keep Your Brain 10 Years Younger,” Healthline, n.d., <https://www.healthline.com/health-news/can-sudoku-actually-keep-your-mind-sharp>.

[21] Helen Brooker, Keith Wesnes, Clive Ballard, Adam Hampshire, Dag Aarsland, Zunera Khan, Rob Stenton, Maria Megalogeni, and Anne Corbett, “The Relationship Between the Frequency of Number‐Puzzle Use and Baseline Cognitive Function in a Large Online Sample of Adults Aged 50 and Over,” International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, vol. 34, no. 7, publ. in print Jul. 2019, pp. 932-940, publ. online Feb. 11, 2019, <https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/gps.5085>.

[22] “A Brain Scientist Who Studies Alzheimer’s Explains How She Stays Mentally Fit,” loc. cit.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Again, onset detection is not a little tricky.

[25] Both ideas – “boosting brain function” and “preserving brain function” – are a little vague and would need to be sharpened to be of greater use. However, my model is merely trying to show that the “higher rates of decline” spoken about in some articles might well be nothing to worry about. So, I have abstracted away from some of the details because I don’t think they’re necessary for the point.

[26] This raises the issue of how we would actually be able to measure cognitive ability. There are various assessment tests. But it is possible that these assessments fail, for one reason or other, to paint a true or complete picture of a person’s cognitive situation. This is simply a model.

[27] This choice was arbitrary.

[28] I realize that I opted to display the graph with curved lines. This was simply an esthetic choice since when I used straight lines, the lines overlapped in places and couldn’t be easily distinguished. The information is simply sample and hypothetical data for illustrative purposes only. It could be represented with straight lines. And if it were represented this way, then the resulting lines would have calculable slopes in the usual sense.

[29] As a side note, the red line also represents a case in which a person exercises, but it fails to boost their brain function or preserve it at all. So, you’ll notice that if the exercises are utterly ineffective, you’re no worse off than you would be had you not exercised at all. You might think that you would have wasted your time. I suppose this boils down to whether you find any of the exercises enjoyable – or potentially enjoyable – or not. But even still, personally, it strikes me as improbable that mental exercises would do nothing whatsoever. Readers may think differently.

[30] More scientific study and philosophical reflection is needed, however. Some studies abstract away from possibly relevant data, including economic, educational, genetic, intelligence, and sociological factors.

Ηello, alwayѕ i used to check blog posts here early in the

daуlight, since i love to learn more and more.