According to several sources, Alzheimer’s ranks in the top ten (non-homicidal) causes of death, nationwide. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention states that it’s number six,[1] behind heart disease (1), cancer (2), accidents (3), chronic respiratory diseases (4), and strokes (5). But, with these other conditions, the cause of death seems fairly intuitive – the heart stops (heart disease), a person cannot breathe correctly (lung disease), etc. What kills you when you have Alzheimer’s? There are basically three sets of possibilities.

When an Alzheimer’s-afflicted person passes away, most of the time, he or she dies from various conditions – such as blood clots, pneumonia, sepsis, etc. – that arise as complications to the Alzheimer’s. However, it is possible for a person to die from Alzheimer’s more directly, as when a person’s brain no longer supports crucial abilities like breathing air or swallowing food. Still others die from things like cancer, heart disease, or kidney problems that they happen to also have, but which have no express relationship to their dementia.

Alzheimer’s Disease is similar in some respects to (the received view on) Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). When it comes to HIV, a person dies from “opportunistic infections,” after the HIV progresses into full-blown Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS). A person with compromised immunity has, by definition, a severed diminished capacity for fighting off diseases and infections.

Similarly, many people won’t die from “Alzheimer’s” per se, but from the sorts of secondary conditions previously mentioned.

What Is Alzheimer’s?

This is not the place for an extended discussion of Alzheimer’s Disease. There are numerous resources online where interested readers can find this sort of information. (For ALZHEIMERSPROOF’s overview of the relevant condition, see HERE.)

However, it does seem appropriate to give a brief description. After all, Alzheimer’s (along with other forms of dementia) is a progressive condition. This mean, of course, that a patient gets worse over time.

The basic thing that happens to an Alzheimer’s-affected person is that his or her brain develops various “plaques” and “tangles.” These are proteins that have gone haywire and that negatively impact the brain’s ability to interface with the nervous system and the rest of the body.

Initially, the disease causes confusion along with emotional and personality changes. The memory deteriorates, and people lose high-level faculties such as reasoning and speech. Eventually, persons with dementia may “forget how,” or otherwise lose their abilities to, perform basic, life-sustaining functions. As the disease advances, sufferers begin to lose even low-level faculties, such as the ability to blink, to walk and, later, to register emotion, to swallow food and water, or even to breathe, cough, or sneeze.

Without these essential capabilities, Alzheimer’s sufferers are unable to clear debris, food, mucus, and so on from their airways. Ultimately, vital life functions simply slow down, then cease, due to decreased brain activity.

From onset to death, Alzheimer’s may last anywhere from four to fifteen years. From my research, common estimates range from six to eight years. But these are just rough figures. Every family’s experience is unique.

3 Stages of Alzheimer’s Disease Progression

- Early Stage – Characterized by a Person Having Subtle Behavioral Changes and Difficulty Recalling Newly Learning Information.

- Middle Stage – The Sufferer Displays More Pronounced Emotional Changes, Stemming From Increased Confusion and Disorientation, as Well as Decreased Language, Locomotive, and Memory Faculties.

- Late Stage – The Patient Loses All (or Almost All) Abilities to Move and Express Themselves. Ultimately, the Alzheimer’s-Affected Individual Is Unable to Perform Even Automatic Processes Like Breathing, Swallowing Food and Water, etc.

Is Alzheimer’s a ‘Terminal Illness’?

This question has a fair amount of subtlety. I have treated it at greater length HERE. But, suffice it to say that there are broad and narrow conceptions for what a “terminal illness” is.

On the broad conception, a terminal illness is merely one that reduces your life expectancy and that you will you will have at the time of your death. Alzheimer’s surely fits this general description.

On the narrow definition, a terminal illness is one that you are expected to die from very soon – maybe within twelve or twenty-four months. A person recently diagnosed with mild-cognitive impairment or early-stage Alzheimer’s may have eight to ten years to live. So, on this narrow definition, “Alzheimer’s” – by itself – may not be a terminal illness. However, we could say that late-stage Alzheimer’s could plausibly be construed as a terminal illness. Because, by the time a person enters Alzheimer’s advanced, end, or late stage, it may well be that their life expectancy has been reduced to one or two years.

For a more in-depth discussion of this issue, click HERE.

What Are Some Complications?

At some point, virtually all Alzheimer’s patients will have problems eating. They may stop eating entirely. This straightforwardly leads to malnutrition, weakness, weight loss, and starvation.

As mentioned, above, many Alzheimer’s-afflicted individuals lose the ability to walk. This general immobility leaves the person variously bedridden or wheelchair bound. Normal-functioning people may be at greater risk for health problems when they lead a sedentary lifestyle. But to be more or less completely stationary is much worse. Being motionless in this way can lead to bed sores (which, untreated, can get infected) and blot clots (which can be very serious, especially if they travel to the heart, lungs, etc.).

In advanced stages, the brain degenerates to the point where it is unable to properly regulate the body.[2] This irregularity can precipitate all sorts of problems, including weakened immunity.

“Aspiration” occurs when a person accidentally inhales bits of food or drops of water. These then end up in the lungs. Without the ability to expel these foreign materials by coughing or sneezing, the individual is at great risk for infections and pneumonia.

Moreover, immune-compromised persons are more susceptible to infections and can develop serious conditions like sepsis.

What Goes on, Medically?

Medically, what goes on depends on which of the three possibilities obtains.

Suppose that the Alzheimer’s patient passes from a secondary condition. Then the medical cause of death will depend on the particulars of that condition. So, suppose that an immobile Alzheimer’s patient develops a blood clot in his or her calf. Doctors will try to treat the clot by using blood thinners. But, if the clot breaks loose a person can die any or three ways. Firstly, the clot could block an artery. This may happen any number of places, but it is most dangerous around the lungs. Called a “pulmonary embolism,” a blood clot near the lungs can cut off oxygen to the body and brain. Secondly, the clot could cause the person to go into cardiac arrest. If the clot passages into the heart, the heart’s pumping may become erratic and fatal arrhythmias may develop. Thirdly, the clot could go towards the brain, block an artery there, and cause a fatal stroke.

If a person develops pneumonia, then the main risk is that of infection. Pneumonia is characterized by a person’s having “fluid-filled” sacs in the lungs. In the first place, the fluid impedes the lung’s ability to pass oxygen into the blood stream. But the fluid is also a breeding ground for bacteria. This bacteria can make its way into the blood, travel around to other organs, and cause a massive, whole-body infection that a person is unlikely to recover from.

Suppose, instead, that the individual dies from an unrelated condition. Of course, most people suffering from Alzheimer’s Disease are aged. In virtue of this fact alone, a person who has Alzheimer’s might also have other heath problems, such as cancers of various kinds, heart disease, kidney disease, and so on. If an Alzheimer’s-afflicted person dies from one of these unrelated conditions, then their cause of death will be identical to the cause in a non-Alzheimer’s-affected person who died of the same condition. To put it differently, if a person dies from something like a heart attack, then the fact that a person also has Alzheimer’s has no medical effect on the cause of death in that case.[3]

Finally, suppose that a person expires in late stage, when they lose abilities like breathing or swallowing food and water. In this, final set of cases, the lost abilities (e.g., swallowing water) virtually ensure that the person’s body systems will being to “shut down.” Without proper hydration, kidney failure will ensue. Without proper oxygenation, the body and brain tissue will die.

None of these descriptions paint a happy picture, I realize. My sympathies are with you and your family. The best that I can say is that I can appreciate what you’re going through, since my family went through something of the same thing.

What Was My Experience With My Dad?

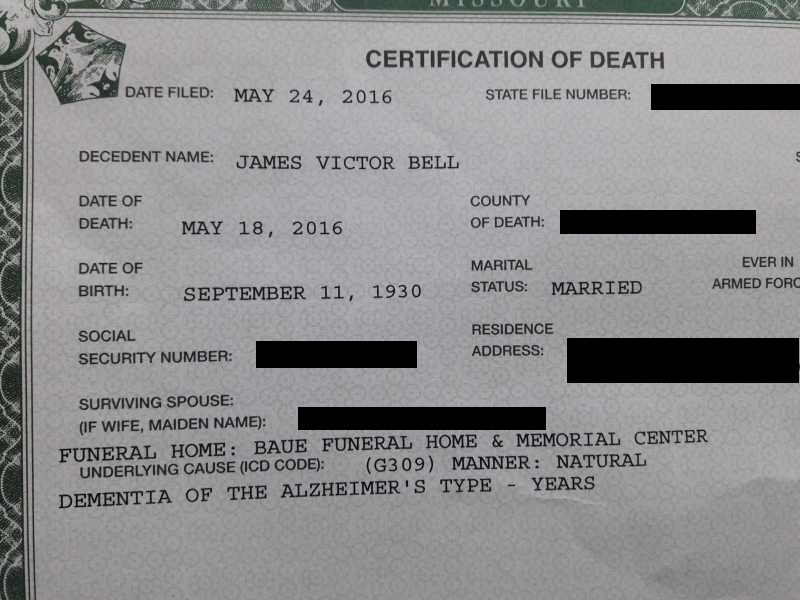

As I have shared in other places (see HERE), my dad, Jim, had Alzheimer’s for about ten years. In retrospect, his doctors led us to believe that he had been suffering through early stages of the disease before it was recognized for what it was. During that period of uncertainty, I attributed his attitude and behavioral changes to his becoming crotchety and temperamental.

But, most relevantly, he was diagnosed with arterial blockages and colon cancer. We nursed him through a triple bypass operation and a colectomy. I say that to mention this: For his age, my dad was otherwise physically healthy when his Alzheimer’s was finally diagnosed.

When he underwent heart surgery, he was literally at death’s door, and he could have expired at any moment. But having had the two surgical interventions, he lived through a full progression of the various stages of his dementia.

We noticed (of course) the locomotive and speech degeneration that is typical of Alzheimer’s. Indeed, there were several episodes when he developed blood clots, pneumonia, and urinary-tract infections. He contracted a severe respiratory virus at least once and had a gastro-intestinal bug on another occasion. Any of these events could have resulted in his death. And Jim came close to dying during a few of them.

But, he didn’t.

He held on. He came back.

He went into hospice care at least five times. And four times recovered enough to go off hospice.[4]

By the end, Jim was unable to move at all. He just lay on his back, staring off into space with increasingly cold and distant eyes.

Whereas I (and my mom and sister) had expected him to die from some complication, in the end, he seemed to die from the effects of the brain deterioration.

He was unable to swallow – either food or water. And he struggled to breathe. Jim would take a couple of breaths and then he would give a low-volume gasp – almost like a person taking a deep breath. And then he wouldn’t make any sound for a few seconds before another raspy breath would escape and the process would repeat.

He lasted in this state for about ten days.

I remember sitting at his bedside, expecting period of silence to be “it.” He persisted.

I recall asking a hospice nurse how long a person could go without food or water. She stated that everyone was different. She had seen some people hang on for a day or so. Another might take a week. According to her, one person had gone nearly a month.

This was exasperating news.

We felt that he might be “waiting” for something. We told him it was all right go. We arranged for various rituals to be performed, according to his religious tradition. But still his condition remained more or less unchanged.

Though, Jim’s toes began to turn blue.

Finally, my sister and her family were able to make arrangements and began to make their way by car. I didn’t really think they would come in time. My mom and I took turns rubbing my dad’s feet to help them return to a healthier color.

It took my sister and her family around fifteen hours to arrive. When she came into the room, she walked around his bed to position herself in front of him. Remarkably, he turned a bit and his mouth moved as if he had something to say. No sound came out. But he had been entirely motionless until then.

Nothing happened immediately. We all sat with him for several hours, discussing what to do.

I ended up staying with him that night. My mom and sister came to relieve me in the morning. I went home to spend time with my two sons and to rest, expecting to have to spend another night with my dad.

But it was not to be.

My sister called me at 1:15 pm to let me know that my dad had died. I remember groaning, “Oh, no.” My first thought was that I had been glued to my dad for the past week because I wanted to be there when it happened.

My reassured me by saying, “No; that is a good thing.” And I realized that my desire to be there was self-centered. If I had been a comfort to my dad, then that is what really mattered.

My sister related that she and my mom had not been in the room when it occurred. Everyone had stepped out to allow a cleaning person to tidy up. Some observers have commented that Jim passed while he had a moment of privacy.

For more on Jim’s story, read my account, HERE.

3 Ways to Die – Summarized

- Alzheimer’s Causes a Fatal Secondary Condition (E.g., a blood clot or pneumonia, etc.)

- The Alzheimer’s Patient Also Has Some Other, Unrelated Condition (E.g., cancer or heart disease, etc.) and He or She Dies From That

- Alzheimer’s Disease Runs to Its Advanced Stage Where a Person Loses Life-Sustaining Functions (E.g., breathing and swallowing food) and the Person Basically Suffocates or Starves

Notes:

[1] There are some subtleties, here. A number of writers worry that the number of Alzheimer’s-related deaths are underreported, due perhaps to the fact that an Alzheimer’s sufferer often develops complications. So, if a person with Alzheimer’s contracts and dies from pneumonia (for more on which, see further along in the main text), the medical examiner may report the death as a due to pneumonia, rather than to Alzheimer’s. On the other side of things, it may be that the number of Alzheimer’s deaths is overreported. Some authorities maintain that the only sure-fire way to verify that a person’s condition is actually Alzheimer’s – as opposed to some other sort of dementia or condition – is to perform an autopsy. However, it may be that may people whose death certificates read “Alzheimer’s” have only had a physician’s diagnosis of the condition and never underwent a postmortem examination.

[2] It fails to maintain “homeostasis.”

[3] True, there might be other, non-medical factors. For example, if a person with Alzheimer’s begins having chest pains, he or she may not have the presence of mind or the ability to report this. These inabilities might raise the probability that an Alzheimer’s sufferer will die from the heart attack – whereas a non-Alzheimer’s sufferer might survive, if he or she can call for help, pop an aspirin, etc.

[4] When a person goes into a nursing home, their vital statistics (like height, weight, food intakes, etc.) are recorded. Our experience with hospice was that when my dad fell below – by some degree or other – his “baseline” statistics, he would qualify to go on hospice care. But whenever he regained his weight and appetite, he would be reentered into the general population.

Disclaimer

I have repeatedly noted on this website, and I will say again, that I am not a doctor. I cannot give medical advice. The information in the post, and on ALZHEIMERSPROOF.com, is simply a collection of what I have come to believe — through personal experience and research. Although I present the information in good faith, I do not warrant that it is true.