Alzheimer’s-Proof Your Diet: Vitamin D and Other Nutrients

The prospect that I might end up like my dad frankly terrifies me. I watched helplessly as he slowly lost his faculties – both mental and physical. It’s no exaggeration to say that Alzheimer’s Disease appeared to strip him of his humanity. If I thought that making changes to what I eat would – or even could – result in improved odds for avoiding dementia in my old age, then I would happily alter my diet.

In fact, some recent scientific research provides an indication – not to say a hope – that such dietary changes might be possible. Amazingly, such modifications are arguably easily implemented.

Vitamin D

Vitamin D is among the candidate nutrients that figure prominently in such a nutritional-reform project. To be a bit technical, the term “vitamin D” actually refers to a group of compounds rather than one single thing.[1] It also turns out that the stuff we call vitamin D is perhaps better described as a hormone that helps to maintain healthy cells as opposed to a “vitamin” in a traditional sense.

However scientists classify it, though, vitamin D interests me because of what it might be able to do for me. In this vein, there is an impressive list of things that vitamin D is believed to help.

According to Medical News Today[2] vitamin D plays an important supporting role in promoting:

- favorable blood pressure readings

- balanced blood sugar

- strong bones

- optimal brain and nervous-system operation

- healthy breast tissue

- excellent calcium absorption (among other metabolic processes)

- robust immunity

- vigorous lung and cardiovascular function

- overall longevity

- uncomplicated pregnancies and deliveries

- normal vision and macular health

To this already extensive and impressive list, let me not forget (no pun!) to add vitamin D’s alleged capability of staving off dementia.

An article from the highly esteemed Mayo Clinic started my journey into finding more research on this possibility. The pertinent article concerned a study from 2014, which showed that people with vitamin-D deficiency were twice as likely to develop dementia in general, and Alzheimer’s in particular.

Predictably, the clinic’s doctors took a cautious stance. They said, circumspectly, that more research was needed before anything conclusive could be declared. For my part, I am not as interested in making causal claims – even true ones – as I am in stacking the deck in my favor, health-wise.

Since discovering the Mayo Clinic post, I have unearthed several other pieces of information outlining correlations between vitamin D and dementia. Sayer Ji’s website, GreenMedInfo, has been an outstanding resource in my investigations.

I have learned that one study, published in 2012 in the scientific journal Neurology, compared scores on a state exam and concluded that low cognitive abilities corresponded with low vitamin D levels. That same year, a study followed almost 500 women for seven years. Experimenters obtained similar findings. Women who were determined to be vitamin-D deficient as the program began, were adjudged more likely to develop Alzheimer’s. A third study from 2012 professedly demonstrated that vitamin D helped to clear the sort of “amyloid plaques” that form in the brains of dementia patients.

Is vitamin D a panacea? When it comes to giving the proverbial “definitive answer,” we should probably agree with the Mayo Clinic’s physicians: more research is needed.

However, when it comes to deciding how to structure my diet, I cannot see much reason to neglect supplementing with vitamin D.

If you too are persuaded that vitamin D might be helpful for you or someone that you love, here are some ways to incorporate it into your life.

How to Get More Vitamin D

The most direct way of obtaining vitamin D is through exposure to sunlight. So, take a walk outside.

I hear you exclaiming: “But I heard that (excessive) sunlight was bad for you!”

First of all, bear in mind that there are 2 types of rays that penetrate the earth’s atmosphere: UVA and UVB. UVA is indisputably a harmful one. UVB, on the other hand, is our natural vitamin-D3 source. UVB rays are readily available during certain times of the year in different locations. Purportedly, the sun needs to be at 50 degrees at or above the horizon. It seems like the winter sun would not be as beneficial as the sun in spring through fall – not that you need a reason beside presumably frigid temperatures to stay inside.

For most of human history we worked and virtually lived our lives outside. You might say that we were, well …made to be in nature. So I am planning on spending lots of time outdoors.[3]

But for those who balk at the idea of getting more “rays,” or for those who are (for whatever reason) otherwise unable to do so, it should be said that vitamin D is also found in numerous foods. It’s available in caviar, egg yolks, fish (of various sorts, including mackerel, salmon, sardines, and tuna[4]), and milk (raw).

Still, even if you’re getting moderate sun exposure and eating fish, you might find it desirable to augment your diet with commercially available vitamin-D supplements.

From what I have read, you want to look for the word cholecaliferol on the label. This form of vitamin D – known as vitamin D3 – appears to be the “best” in terms of things like efficacy, potency, and absorption.[5]

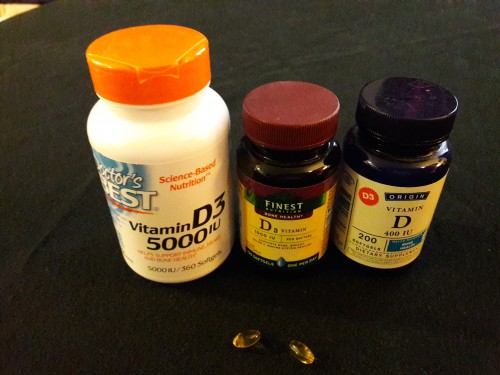

My chosen brand in the past was NOW, which makes a whole assortment of vitamin D3 capsules.[6] One that I have purchased repeatedly is NOW’s 5,000IU offering. Recently, due to the slightly lower price, I have switched to Doctor’s Best, also in a 5,000IU amount.

How Much Should You Take?

I need to emphasize that I am neither a doctor nor a nutritionist. Presumably, the most accurate way to arrive at a dosage amount would be to have your levels of vitamin D tested, and then (on the assumption that you are not already where you need to be) to have a customized recommendation as to how to move that measured level into its ideal range. Obviously, I cannot administer such a test on anybody and I cannot make any sort of customized recommendation.

I can, however, report my research findings and disclose my own practices (which you may take or leave).

Let me begin with the former. Alternative medical “guru” Dr. Andrew Weil suggests that supplementing with 2,000 IU each day ought to suffice as a good supplementary starting point for most people.

For me, personally, 5,000 IU is my go-to amount during the winter months, when sunlight is on the decline and time outdoors is hard to come by. I am by no means a nutritionist, but I take 1 capsule daily as a maintenance dose. To put it another way, I take one 5,000 IU capsule every day in order to keep my vitamin D3 levels up. If I feel myself falling ill (for example, with a respiratory illness), I may double up the dosage or take a single dose more than once.

I do also keep other amounts of vitamin D3 on hand. Right now, I have 1,000IU and 400IU products from Finest Nutrition and Origin. My idea is to augment, when necessary, my vitamin D3 levels during times (perhaps during the summer), when I might feel under-the-weather or be otherwise stuck inside and unable to get my daily sun exposure.

Some sources indicate that vitamin D3 should be taken alongside vitamin K, in order to aid absorption. I have been a bit lax in terms of following this advice. But now that I am reminded of it, maybe it’s time to make a change.

Other Nutrients

Looking into supplements reported to help in preventing Alzheimer’s, you quickly find out that vitamin D is not the only substance to consider. Four other figure conspicuously in the pertinent literature.

Folic Acid is a water-soluble vitamin also known as Folate or B9. Folate occurs naturally in vegetables like asparagus, avocados, beans (dried), beets, broccoli, lentils, peas, and spinach. It also turns up in fruits – chiefly bananas – as well as in liver. Technically, folic acid is the synthetic form of folate, and it is contained in many fortified foods and available separately as a supplement.

Folic acid and folate aids in:

- maintaining brain and nerve function

- generating red blood cells

- and generally helping your cells to reproduce and combine DNA appropriately

(This latter responsibility of the cells, if done incorrectly, could contribute to the growth of cancers because it can lead to damaged or mutated DNA.)

Vitamin B12 is also a water-soluble vitamin. Called Cobalamin, B12 is found in beef liver, sardines, Atlantic Mackerel, lamb, wild-caught salmon, nutritional yeast, feta cheese, grass-fed beef, cottage cheese and eggs.

Available in chewable tablets, regular tablets, and liquid, is important in:

- making red blood cells

- maintaining brain and nerve function

- supporting energy levels

- protecting the cardiovascular system

- improving bone density and strength

A deficiency in B12 could block folate so that it can’t change into its active form. If folate can’t change into the active form, it can’t do the job of aiding the cell during DNA reproduction. This, in turn, can lead to DNA corruption.

Magnesium is a mineral that is found in spinach, chard, yogurt, almonds, cashews, pumpkin and sunflower seeds, avocados, bananas, black beans and dark chocolate.

Magnesium (in aspartate, carbonate, citrate, glycinate, L-threonate, orotate, oxide, malate, and taurate forms[7]) supports:

- calcium and potassium absorption[8]

- nerve and neurotransmitter function

- blood-sugar control

- blood-pressure regulation

- maintenance of energy levels

Fish oil comes, funnily enough, from “oily” fish – such as wild-caught salmon, herring, tuna and sardines. Fish oil is a wonderful source of omega-3 fatty acids.

Studies have shown that fish oil, and omega-3 fats, yields positive benefits in these areas:

- Alzheimer’s Disease

- anxiety

- arthritis

- cancer

- cardiovascular disease

- diabetes

- eye disorders

- immune function

Additional Supplements to Consider

Although the jury is still out, the following might also be worth your time and attention:

Vitamin E is a fat-soluble vitamin found in almonds, asparagus, broccoli, butternut squash, chard, olive and palm oils, spinach, sunflower seeds, sweet potatoes, trout, and wheat germ. It is an antioxidant that prevents damage to specific and important fats in your body.

Vitamin E benefits us in virtue of its abilities to:

- Assist our bodies’ regulation of cholesterol

- Support the repair of skin damage

- Promote balanced hormone levels and healthy muscles

- Improve vision (at least, in conjunction with vitamin C, beta carotene and zinc)

- Protect against heart disease

- And, crucially for the present discussion, slow the progression of Alzheimer’s Disease

Ginkgo (ginkgo biloba[9]) is considered an herb. The stuff comes from an ancient tree whose benefits have been known in Chinese medicine for thousands of years. It may be consumed as a tea (for example, as a hot infusion) or in capsule form. In general, ginkgo has become quite well known among herbalists as an anti-inflammatory as well as a brain-function and nervous-system enhancer. Given this folk reputation, it is not difficult to see why it may be beneficial to dementia sufferers – and to those who wish to avoid that description.

Alleged benefits of gingko include:

- Conservation of visual acuity (possibly along with beta carotene, eyebright, and lutein)

- Improved cognitive function (especially increased memory capacity and heightened concentration)

- Maintenance of energy levels

- Promotion of positive mood (perhaps similarly to St. John’s Wort and “SAMe,” S-Adenosyl methionine)

- And reduction of dementia risk

Turmeric is a powerhouse herbal whose potency – over a wide range of conditions – has been suggested to be superior to pharmaceutical-based medicine.[10] Turmeric shows up on too many lists to adequately summarize here. Suffice it to say that turmeric boasts benefits as a(n):

- Anticoagulant

- antidepressant

- anti-inflammatory

- cancer treatment

- cholesterol regulator

- pain reducer (particularly for arthritis)

It is also taken in supplement form. Black pepper (bioperine) should be added to assist the bioavailability of the curcumin – one of turmeric’s principal active ingredients. There are two option. One option is to get a turmeric-pepper combination product. The other is to acquire bioperine individually.

CoQ10 is an element that is naturally produced in our bodies. As we age, that production decreases. Fortunately, Coenzyme Q10 is found in many foods like grass-fed beef, cage-free eggs, free-range chickens, strawberries, herring, broccoli, cauliflower, beans, nuts, oranges and rainbow trout.

Many positive benefits are touted for CoQ10. It:

- boosts energy levels

- promotes healthy cardiovascular systems and lungs

- reduces muscle diseases

- stabilizes blood sugar

- and, of course, may help cognitive disorders like Alzheimer’s

_________________________________________________

Notes:

[1] Specifically, they are fat-soluble steroids.

[3] There is some evidence that vitamin D production can be stimulated through light exposure to tanning lamps. For more information on that, in my view, back-up option, see here. Besides being pricey (see Sperti’s “Fiji Sun” model), artificial light just pales (okay, maybe that is a little pun) in comparison to the real McCoy.

[4] Of course, you should keep in mind the adage “all things in moderation.” Tuna, amongst other fish types, may contain disadvantageous things like mercury.

[5] Food that is labeled “fortified with vitamin D” often contains D2 (ergocalciferol), a form of D which your body cannot absorb as well as D3. This may be due, on part to the source of each form. Vitamin D2 is plant-based, while D3 is animal-based (fish usually). In any event, the superiority of D3 over D2 has led to some writers referring to D3 as the “real” form of vitamin D. I won’t take a position on that, here. I simply want readers to be aware of the terminology.

[6] Though, I have begun to consider giving preference to products with bases of pure safflower oil instead of soybean or coin oil. This is due to GMO worries – another can of worms entirely. Readers who share this concern might take a look at Bluebonnet, Nature’s Plus, and other companies that manufacture such safflower-based products.

[7] Oxide and carbonate are generally inexpensive, but are also (supposedly) poorly absorbed. I have been supplementing with citrate and malate forms – alternating in order to increase the bioavailability of each form. I have read good things about aspartate, orotate, and taurate in terms of heart health. However, for Alzheimer’s support – and possible prevention – my money is presently on glycinate, L-threonate, and malate, due to their association with cellular-energy and cognitive support.

[8] In fact, most magnesium is found in the bones.

[9] Note that “ginkgo” is alternately rendered “gingko.” While I disfavor this spelling for some perhaps veiled psychological reason, it does comport more closely with the way that I pronounce the word.

[10] Herbalists and naturopaths sometimes disparagingly refer to this sort of medicine as “allopathy.”