Researchers have not yet been able to say definitively what the cause of Alzheimer’s disease is. But, among the candidate causes discussed is oxidation in the body – also called “oxidative stress.”

I want to survey the antioxidant potential of sixteen (16) herbs that you might have on your spice rack at home.

The Relevance of Oxidation

Oxidative stress dovetails with Alzheimer’s disease in several respects.

Firstly, patients who already have Alzheimer’s disease have problems with accelerated oxidation. They have more oxidative stress in their brains.

Secondly, many readers may also be aware that one of the primary characteristics of Alzheimer’s disease is that there is an abnormal accumulation of beta-amyloid and tau protein deposits, which aggregate between – and inside of – nerve cells, gumming up the neural “works.” Well, this abnormal deposition of protein has been speculated either to be the result of an increase in “free radicals” or a decrease in antioxidant defenses inside of some people’s bodies. In other words, it’s the result of oxidation.

But that raises the question: Are antioxidant therapies for Alzheimer’s disease viable?

In attempting to answer this question, we should be mindful of the fact that herbs can be excellent sources for antioxidant. And, as I mentioned at the outset, many of these versatile plants can be found in your kitchen.

In this article, I’ll list sixteen of the most common. (In a follow-up post, I’ll provide a further sixteen that, while less common, are still available.)

Caveats

Obviously, I’m not guaranteeing that you will have all – or even any of – these on your spice rack. Various starter sets will likely include some elements that I don’t write about. Contrariwise, your set may fail to have some component that I do discuss.

Additionally, these profiles are not exhaustive. Moreover, not every example of these herbs will have exactly the same chemical constituents or in the same amounts. It often depends on how the plants are grown, what weather conditions were like, how they were harvested, how the extract was harvested, how was stored, etc. Numerous peer-reviewed scientific journals contain more detailed information on herbs, in general, and on their antioxidant constituents, specifically.

16 Common Antioxidant Herbs You Have on Your Kitchen Spice Rack

Spice #1: Basil[1] (Ocimum basilicum)

Like most of the herbs surveyed here, basil is a good source of vitamins – many of which actually are antioxidants, themselves. But what I’m going to be concerned with is some of the other antioxidant chemicals that are found in these plants.

I have come up with these little graphics with a list of antioxidants. I’m calling these the “antioxidant profile.”

In some cases, an herb’s antioxidant activity can’t be explained solely by the presence of any single compound on the list. In other words, following this line of thinking, it’s not just eugenol, but it’s eugenol in conjunction with all of the other chemicals contained in basil.

(Note: eugenol is more abundantly present in oil of clove. See Part 2.)

This propensity of antioxidants to complement and mutually amplify one another is referred to as “synergism.”

In addition to basil’s significant antioxidants, the herb has also been shown to increase both “memory retention” and “memory retrieval” in experiments on mice.[2]

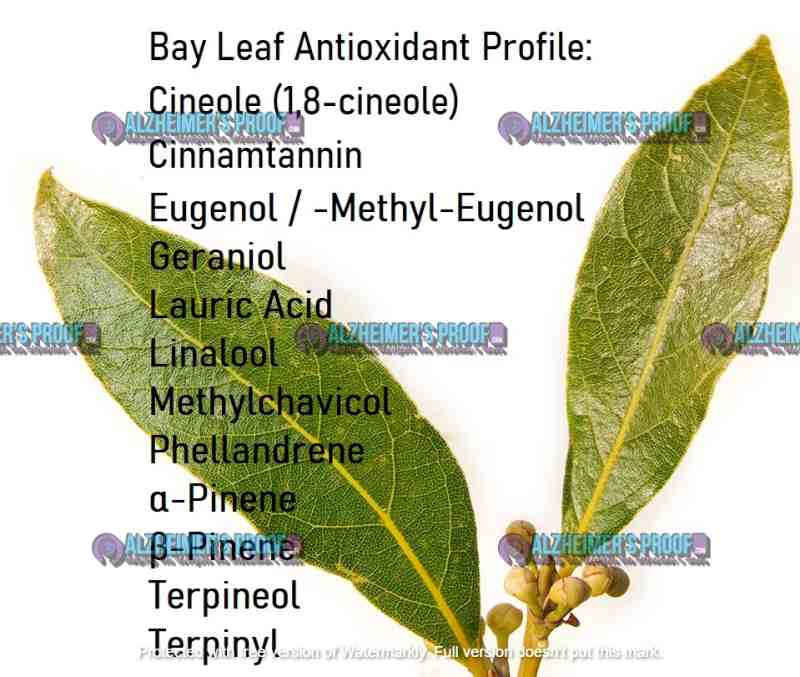

Spice #2: Bay Laurel Leaves (Laurus nobilis)

You can see that my list for bay leaves is a little bit less expansive than it was for basil. sale being the primary one.

Nevertheless, bay laurel essential oil is a rich source of natural antioxidants. In fact, the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant potential of “laurel extracts is very significant,” particularly in relation to pathologies such as “Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and atherosclerosis.”[3]

Spice #3: Black Pepper (Piper nigrum)

This one is really interesting to me. I’m fascinated that this is on the list because even people who don’t have a “collection” of herbs and spices probably have a salt and pepper shaker!

So, it’s amazing that pepper – regular pepper – may have many health-promoting qualities. And it may be highly relevant to Alzheimer’s prevention and treatment.[4]

For example, it’s full of antioxidants.

Piper nigrum’s signature component is something termed “piperine.” You don’t have to go further than the title of one Food-and-Chemical-Toxicology article to get a sense of why this is constituent is so exciting. “Piperine, the main alkaloid of …black pepper, protects against neurodegeneration and cognitive impairment in animal model[s] of cognitive deficit[s] like …Alzheimer’s disease.”[5]

It might be worthwhile to develop a taste for black pepper – if you don’t have one already! Sprinkle a little on your food next dinnertime.

Not only is a good antioxidant, in general, but it actually helps reduce high-fat-intake-induced oxidative stress, specifically.[6] Obesity, and consumption of high-fat diets are both known to be risk factors – that is, increase risk – for Alzheimer’s.

I get into this further in Part 1 of my YouTube-video series on sugar and dementia. (Watch Part 1, HERE.)

But, since black pepper is also purported to have acetylcholinesterase activity,[7] Piper nigrum is also an excellent and promising candidate for multi-target Alzheimer’s-disease therapies.

(And… if you want to get more into acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, I have separate YouTube videos on that subject. For a rudimentary explanation of how acetylcholinesterase inhibitors are supposed to work, see HERE. On the perhaps far-fetched and – as far as I know – merely theoretical possibility that a natural “acetylcholinesterase deficiency” might be beneficial in avoiding Alzheimer’s, see HERE. Finally, on the six, Food-and-Drug-Administration-approved Alzheimer’s drugs – five of which have acetylcholinesterase-inhibiting functions – see HERE.)

It’s worth observing that it’s not just black pepper that is reported to deliver positive health effects. The Piper genus has some 2,000 species of plants.[8] It is plausible to think that at least some of these will have effects similar to those of black pepper just rehearsed.

Spice #4: Cayenne / Paprika (Capsicum annuum)

Speaking of varieties of pepper, cayenne is another one commonly locatable on kitchen spice racks.

Rich in antioxidants, Cayenne’s main constituents include ascorbic acid, which is (of course) the more “sciency” name for Vitamin C. (By the way, for more on Vitamin C, glance see further down in this article.)

Vitamin C isn’t this pepper’s only arrow in its nutritional quiver. Cayenne also contains a healthy quantity of calciferol, that is, Vitamin D.[9]

Cayenne is known, in part, for is its antidiabetic effect.[10] Of course, diabetes may increase a person’s risk of Alzheimer’s.[11]

I’ll add that some people might have a cannister labeled paprika in their herbal starter packs. Now, I am not a chef, so this is not a culinary observation, but… cayenne and paprika are very similar. In fact, they’re similar enough that, from our standpoint, they can be considered readily interchangeable.[12]

So, for example, paprika is an antioxidant. It contains a variety of compounds, including Vitamin A – or “retinol” – and some other carotenoids, similarly to cayenne. It’s rich in antioxidants.[13]

You can see some validation of this in the article with the somewhat forbidding title, “Binding Antioxidant and Antiproliferative Properties of Sweet Paprika.”[14]

I’ll presently toss in a little caveat. Weather conditions as well as the various, possible ripening stages of individual peppers are going to impact the chemical constituents of these herbs. In the article cited in my footnote, you can see this point in reference to paprika.[15] However, as hinted at in my “disclaimers,” similar statements considerations apply to any of the herbs surveyed.

Spice #5: Cinnamon (Cinnamomum verum)[16]

Cinnamon is loaded with antioxidants, according to the commonly cited website Healthline.[17]

In some ways, cinnamon’s antioxidant effects are similar to those of black cardamom (Amomum subulatum),[18] which I’ll get into in Part 2. (Again, to see this presentation in a YouTube-video format, see HERE.)

Spice #6: Coriander Seeds [19] (Coriandrum sativum)

Coriander seeds have potential as natural antioxidants.[20] In fact, in addition to coriander’s ability to counteract oxidative stress, the seeds also show antihyperglycemic activity.[21] This makes Coriandrum sativum yet another potential herbal prophylaxis against diabetes. (And this, in turn, may help to reduce a person’s risk of dementia.[22])

Beyond these properties, “Coriandrum sativum seed extract” appears directly relevant to Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia (for example, Multi-Infarct Dementia, also called “Vascular Dementia”) in virtue of its observed “ameliorative effects on memory impairment in… mice.”[23]

To put it slightly differently, it can possibly “[repair] memory deficits”[24] – which is cause for excitement!

Spice #7: Cumin (Cuminum cyminum)

“…[C]umin is a potent antioxidant.”[25]

Its constituents include beta-carotene, cineole, and limonene.

According to an article in the peer-reviewed journal Pharmaceutical Biology, cumin also has antistress potential. But, interestingly, especially for the focus of this website, the authors enthuse that cumin also has “memory-enhancing activity.”[26]

They wrote: “This study provides scientific support for the antistress, antioxidant, and memory-enhancing activities of cumin extract and substantiates that its traditional use as a culinary spice in foods is beneficial and scientific in combating stress and related disorders.”[27]

It happens to be an excellent stand-in for coriander. So, if you don’t have coriander seeds, but you do have cumin, you’re in luck. Not only can you expect that cumin is substitutable from a culinary standpoint, but – as alluded to – it also can be used as a stand-in from the standpoint of antioxidant profiles.

Spice #8: Garlic (Allium sativum)

Speaking of those antioxidant profiles, garlic has a unique one.

Among its noteworthy chemical parts, garlic’s “signature” antioxidant is something called allicin.

Firstly, allicin is being investigated for its possible dual ability to “reduce neuronal death and ameliorate …spatial memory impairment in Alzheimer’s disease models.”[28]

Additionally, allicin also holds promise as an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor[29] – which is the main therapeutic action of the majority of Alzheimer’s drugs – including the preeminent donepezil (sold as Aricept) – currently prescribed.

We already touched on this a bit with black pepper (see above). And we’ll get into it again when we talk about sage (see below), which is also reported to have exceptional acetylcholinesterase-inhibiting activity.[30]

(For my YouTube video on how acetylcholinesterase-inhibiting pharmaceuticals work, click HERE. For my presentation on the six FDA-approved for Alzheimer’s, see HERE.)

In addition to its own antioxidant constituents, Aged Garlic Extract (AGE) has “the ability …to increase the levels of some antioxidant enzymes.”[31]

Among other things, garlic also has a storied history as an antibacterial agent. For more on the herb that, before Alexander Fleming arrived on the scene, was referred to “Russian Penicillin,” see, for example, the article “Extracts From the History and Medical Properties of Garlic.”[32]

Spice #9: Ginger (Zingiber officinale)

“Ginger is loaded with antioxidants…”.[33]

Recalling from our discussions of cayenne and cinnamon that diabetes is an Alzheimer’s risk factor, it’s also notable that “[g]inger has been shown to possess anti-diabetic activity in a variety of studies.”[34]

It also turns out that ginger has health-giving properties that are particularly relevant to females of the species. According to the peer-reviewed journal Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine: “[G]inger is a potential cognitive enhancer for middle-aged women.”[35]

Finally, for Alzheimer’s, in particular, “Z. officinale may be a promising source of AChE [i.e., acetylcholinesterase – editor] inhibitors for Alzheimer’s disease.”[36] Indeed, some researchers think ginger may spark new insights into multi-targeted pharmaceutical approaches.[37]

Spice #10: Mustard (Brassica nigra)

It’s easy to dismiss mustard as a mere condiment. But, in fact, “Brassica nigra” is a remarkable “natural food source for antioxidants.”[38]

Healthline elaborates, stating: “Mustard contains antioxidants and other beneficial plant compounds thought to help protect your body against damage and disease. [i]t’s a great source of glucosinolates, a group of sulfur-containing compounds found in all cruciferous vegetables, including broccoli, cabbage, Brussels sprouts, and mustard.”[39]

Its antioxidant profile includes carotenes and kaempferol.

In the article titled “Kaempferol Attenuates Cognitive Deficit Via Regulating Oxidative Stress and Neuroinflammation…,”[40] appearing in the scientific journal Neural Regeneration Research, investigators report “that [kaempferol] may be a potential neuroprotective agent against cognitive deficit in [Alzheimer’s Disease].

As one of the most popular and widely used spices in the world, mustard is readily incorporated into a wide variety of dishes, recipes, and other culinary applications.

That said, however, bear in mind that various mustard-based preparations may include other ingredients besides the bare mustard seeds. Though, admittedly, some of these – for example, turmeric (see my YouTube videos HERE and HERE) and vinegar – may have salubrious properties of their own.

Spice #11: Nutmeg (Myristica fragrans)

Nutmeg is an interesting entrant to this list. First, let’s look at its “pluses.”

Predictably, the stuff “[c]ontains powerful antioxidants.”[41] As Healthline puts it: “Nutmeg contains an abundance of antioxidants, including plant pigments like cyanidins, essential oils, such as phenylpropanoids and terpenes, and phenolic compounds, including protocatechuic, ferulic, and caffeic acids.”[42]

Among its various “catechins,” and other assorted constituents – which together give it a free-radical-scavenging efficiency – is a unique chemical called “myristic acid.”

In one experiment, which involved feeding mice a “ketogenic diet …rich in myristic acid,” the studied diet “…significantly reduced total brain Aβ levels by approximately 25%.”[43]

Of course, the phrase “brain Aβ levels” refers to the pathological accumulation of junk, known as “beta-amyloid protein,” in the brains of Alzheimer’s suffers. These protein deposits are believed by some researchers to be the at-bottom cause of the dread disease. But, the jury is still out.

(For my own discussions of candidate Alzheimer’s-Disease causes, I invite you to see my WRITTEN ARTICLE elsewhere on this website or, if you’d prefer, view one of my early YOUTUBE-VIDEO efforts.)

Now… onto a few significant “minuses.”

In a New York Times article titled “A Warning on Nutmeg,” the author points us to the historical fact that, “[i]n the Middle Ages, it was used to end unwanted pregnancies.”[44]

This past employment as an herbal abortifacient would probably be little more than a footnote, were it not for the fact, reported by the Journal of Medical Toxicology, that there is such a thing as “nutmeg poisoning.”[45]

And this leads us to the somewhat darker side of nutmeg’s properties: myristicin’s potentially toxic effects.[46]

The concern shouldn’t be overstated, however. These poisoning cases are rare. They tend to involve teenagers horsing around. So, you don’t necessarily have to worry – for example, if you’re following quantity information in a tried-and-true recipe.

Still, interested persons should proceed with caution, since there’s little to go on in terms of precise information regarding how much nutmeg may be needed to cause some of the nastier effects (like hallucinations, nausea, and vomiting).

The New York Times says: “It takes a fair amount of nutmeg — two tablespoons or more — before people start exhibiting symptoms.”[47] That quantities of this sort (two tablespoons or more) are required is underscored by some of the poisoning reports available.[48]

Healthline suggests that doses can be less and still result in adverse events. In the article “High on Nutmeg,” writer Eleesha Lockett tell us: “According to the case studies from the Illinois Poison Center, even 10 grams (approximately 2 teaspoons) of nutmeg is enough to cause symptoms of toxicity. At doses of 50 grams or more, those symptoms become more severe. Like any other drugs, the dangers of nutmeg overdose can occur no matter the method of delivery.”[49]

(For more on this, see my YouTube video, HERE.)

Just handle nutmeg with care. For example, use only as directed by trusted recipes, and keep it out of reach of kids, teenagers, and the cognitively impaired.[50]

Spice #12: Oregano (Origanum vulgare)

“Oregano is rich in antioxidants…”.[51]

A glance at my “profile” for oregano reveals a plethora of powerful, constituent antioxidants, including rosmarinic acid – a compound also found in lemon balm (Melissa officinalis), peppermint (Mentha × piperita), rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis), sage (Salvia officinalis), and thyme (Thymus vulgaris) – and which, in addition to its antioxidant capabilities, “…possesses many biological activities including …anti-inflammatory, anticancer, antiviral, antibacterial, and neuroprotective effects.”[52]

“Dietary intake of oregano oil has been reported to significantly delay lipid oxidation in animal models…”.[53]

One Science Daily post humorously puts things this way: “In what may be good news for pizza lovers and Italian-food connoisseurs everywhere, the herbs with the highest antioxidant activity belonged to the oregano family. In general, oregano had 3 to 20 times higher antioxidant activity than the other herbs studied,” according to at least one American-Chemical-Society investigation.[54]

Spice #13: Rosemary (Salvia rosmarinus / Rosmarinus officinalis)

Rosemary has “potent antioxidant properties” which “have been mainly attributed to its major diterpenes, carnosol and carnosic acid, as well as to the essential oil components”[55] – names for some of which you can read on the “dossier” that I have prepared.

We looked at another, characteristic antioxidant component – namely, rosmarinic acid – when we covered oregano, above.

Rosemary is quite noteworthy. In fact, I have two video presentations dedicated to it (viewable HERE and HERE), including one (ßthe second link!) where I (unofficially!) name it my pick for the second-best “Alzheimer’s herb” – just behind Gingko biloba.

Suffice it to say that rosemary is one of those “powerhouse” herbs that appears to be capable of attacking Alzheimer’s from multiple angles, including: providing “…general antioxidant-mediated neuronal protection,” guarding against “brain inflammation,” and even possibly hindering “amyloid-beta (Aβ) formation.”[56]

(Recall that nutmeg was alleged to have a similar, Aβ-inhibiting action. For a review, see the relevant section, above. And, for similar remarks about sage, continue, below!)

Spice #14: Sage (Salvia officinalis)

As Healthline puts it: Sage is “Loaded With Antioxidants”![57] In fact, the herb reportedly “…contains over 160 distinct polyphenols, which are plant-based …antioxidants…”.[58]

Like oregano and rosemary before it, sage also contains nonnegligible quantities of rosmarinic acid (see the writeup on oregano for details). But it also has salvianolic acid, a chemical that is somewhat unique to Salvia plants.

The widely studied Red-Sage species, Salvia miltiorrhiza, for example, has “Salvianolic acid B (Sal B),” a “major and …active anti-oxidant …[that] protects diverse kinds of cells from damage caused by a variety of toxic stimuli.”[59]

Though, I hasten to add that “…salvianolic acid” shows up as one of the “major components” in “…analyzed samples of S. officinalis…,” or garden-variety sage, as well.

The remarks made in one scientific article are worth quoting at length.

“Amongst many herbal extracts, Salvia species are known for the beneficial effects on memory disorders… S. officinalis (common sage), Salvia lavandulaefolia (Spanish sage), and Salvia miltiorrhiza (Chinese sage) have been used for centuries as restoratives of lost or declining mental functions such as in Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

“…In AD, the enzyme acetyl cholinesterase (AChE) is responsible for degrading and inactivating acetylcholine, which is a neurotransmitter substance involved in the signal transferring between the synapses. AChE inhibitor drugs act by counteracting the acetylcholine deficit and enhancing the acetylcholine in the brain. …Essential oil of S. officinalis has been shown to inhibit 46% of AChE activity at a concentration of 0.5 mg/ml.

“…A study shows that S. officinalis improves the memory and cognition… A randomized, double-blind clinical study has shown that an ethanolic extract from common sage (S. officinalis) as well as Spanish sage (S. lavandulaefolia) is effective in the management of mild to moderate AD…”

“…The cytoprotective effect of sage against Aβ (amyloid-beta plaques) toxicity in neuronal cells has also been proven by …a study which provides the pharmacological basis for the traditional use of sage in the treatment of AD.”[60]

Therefore, sage – along with other plants like gingko, rosemary, and saffron – belongs high on any list of possible herbal Alzheimer’s interventions.

Let me interject, at this point, that if you want more detailed information on or about any of these herbs, then I would invite you to do a little bit of research yourself on PubMed.

First of all, many articles specify more of the antioxidant constituents than I do.

Secondly, as just illustrated by the previous, long quotation, numerous scholarly articles excavate the therapeutic potential of these spices much more completely – and expertly – than I can do in this space.

(However, for a nontechnical introduction, I invite you to check out my own treatment of sage on YouTube, HERE.)

(For a refresher regarding the significance of this activity for Alzheimer’s Disease, see the entries for black pepper and garlic, above. See also: my YouTube presentations on the function of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, HERE; hypothetical “acetylcholinesterase deficiency,” HERE; and FDA-approved Alzheimer’s drugs which have acetylcholinesterase-inhibiting functions, HERE.)

Spice #15: Thyme (Thymus vulgaris)

Regarding thyme, one website reports: “It turns out that this useful kitchen herb is also a high-antioxidant food.”[61]

In fact, thyme – or, at least, its essential oil – is arguably one of the most potent herbal antioxidants. One set of authors reports: “The best antioxidant[62] was T. vulgaris oil.”[63]

And among thyme’s most important constituents – a summary of which you can see in the “profile” that I prepared – is thymol, itself one candidate (on a short list) for the title most powerful antioxidant.

One journal states: “Thymol, carvacrol, and eugenol are the most powerful antioxidants…”.[64]

Thymol is so potent that even “waste thyme extract can… be used as an antioxidant either in food or pharmaceutical emulsions…”.[65]

In terms of Alzheimer’s-Disease relevance, I note that “…thymol decreased the effects of Aβ on memory and could be considered as neuroprotective.”[66]

On top of all this, thyme also displays antimicrobial properties.[67]

(For more on thyme, including a segment on borneol (a constituent that is able to improve the transportation of other therapeutic compounds into the brain) see the YouTube version of this presentation, HERE.)

Spice #16: Turmeric (Curcuma longa)

This herb is more widely known – and regarded – for its potent anti-inflammatory properties.[68]

But, make no mistake, “[t]urmeric is a powerful antioxidant,” also.[69]

The key component is something called “curcumin.” Now, the relationship between curcumin and turmeric is a bit tricky, especially when it comes to supplements. Curcumin has been thoroughly studied for its health benefits – which are numerous.

But, by itself, curcumin does not have the same health benefits from a practical standpoint, because it doesn’t get absorbed well in the digestive tract.

An article in USA Today makes the point.

“Curcumin is a nutritional compound located within the rhizome, or rootstalk, of the turmeric plant. An average turmeric rhizome is about 2% to 5% curcumin. …[I]t’s the curcumin …that has the powerful health benefits. …You would have to take hundreds of [turmeric] capsules to get a clinically studied amount of curcumin. …[But p]lain curcumin extracts are poorly absorbed in the intestinal tract.”[70]

Synergy

One possible workaround arguably depends upon the concept of synergism – mentioned earlier. Recall that this has to do with the idea of “combining” or “pooling” potencies.

So, for example, curcumin can be taken with another of turmeric’s constituents, namely, aromatic turmerone, sometimes abbreviated as “ar-turmerone.”[71]

Another possibility is a combination of curcumin and black pepper, the common spice discussed earlier in this article. “[P]iperine is the major active component of black pepper and, when combined in a complex with curcumin, has been shown to increase bioavailability by 2000%.”[72]

A further illustration of the power of synergy is offered by the Journal of Agricultural Food Chemistry, where we read the following. When sage and thyme are combined, antioxidant constituents, including “[c]arnosol, rosmanol, epirosmanol, isorosmanol, galdosol, and carnosic acid” together “exhibited remarkably strong activity, which was comparable to that of alpha-tocopherol.”[73]

“Alpha-tocopherol is the most active form of vitamin E in humans.[74] It is also a powerful biological antioxidant. Vitamin E supplements are usually sold as alpha-tocopheryl acetate, a form that protects its ability to function as an antioxidant.”[75]

Blends

And… don’t forget about spice blends! Many blends provide you with these common herbs in combination.

For instance, curry powder frequently includes ingredients such as coriander, fenugreek, ginger, and – of course – turmeric.

Chili powder might have garlic in addition to cayenne or paprika.

Italian-seasoning blends are typically going to include basil, garlic powder, oregano, Rosemary, thyme, and so on. Sometimes there’s an assist from things like marjoram or parsley – both of which I get into in part 2. (See HERE.)

There are a number of other blends, of course. For example, there’s poultry seasoning, which can have oregano, sage, and rosemary, but also secondary constituents like black pepper and marjoram.

My point in mentioning blends in these cursory comments is simply this.

Even if you look at your spice rack see discover that you don’t have most – or any – of the sixteen herbs expressly named on my list, if you have a few blends, you might find that you have more than you think you do.

Vitamin C

As a coda, I’ll add that many – in fact, nearly all – of these herbs also include vitamins. In conversations about antioxidants, one of the most significant vitamins is Vitamin C, or ascorbic acid.

Take thyme, for example. Thyme is frequently touted as a significant source of vitamin C. In its article “20 Foods That Are High in Vitamin C,” Healthline reports that “[o]ne ounce (28 grams) of fresh thyme provides 45 mg of vitamin C, which is 50% of the D[aily]V[alue].”[76]

Of course, you’re probably unlikely to consume that much thyme at one sitting.

Moreover, note that the article in question specifically mentions fresh thyme – as opposed to the dried stuff. It’s arguable that fresh herbs are often higher than their dried counterparts in terms of vitamin content, but lower in terms of other antioxidants – or, at least, in terms of measured, overall antioxidant potency.[77]

(I plan on tackling the vexed topic of “ORAC values” in another place.)

Bottom line: just be aware that many of these herbs can deliver some vitamin content. In fact, every one of the herbs that I survey, here, is reported to have some Vitamin-C content.

For More Information

Where can you go for more?

- PubMed is a publicly searchable database of scholarly articles, many of which (though, not all) are posted in full-text format. Just use search strings such as <“antioxidant” + [your favorite herb]>. PubMed is accessible, HERE.

- Among the numerous, informative articles that you may find is an offering like this: “Antioxidant Activity of Spices and Their Impact on Human Health: A Review.”[78]

- That article is actually published by the international, peer-reviewed, academic journal Antioxidants – located HERE – which, as its name suggests, focuses on the topic that has occupied us in this post.

- Additionally, though, my website and YouTube channel are sources for basic introductions to many topics in the vicinity. Some of the titles that readers may find interesting include:

- “Antioxidants on Your Kitchen Spice Rack, Part 1” (16 Common Herbs)

- “Antioxidants on Your Kitchen Spice Rack, Part 2” (16 Less-Common Herbs)

- Alzheimer’s Herbs, Part 1: “Top 10 Ayurvedic Herbs” (except for turmeric!)

- Alzheimer’s Herbs, Part 2: “10 Miscellaneous Brain-Health Herbs” (including sage)

- Alzheimer’s Herbs, Part 3: “Top 5 Herbs for Alzheimer’s Disease” (turmeric is in this one!)

- All 25 of the herbs in the three installments just mentioned appear in a written article on my website, available HERE.

- Finally, I’ll mention my YouTube presentation on “Rosemary” (a dedicated, early video I made on this spice)

[By Matthew Bell]

Notes:

[1] Basil is sometimes referred to as “Sweet Basil.”

[2] Shadi Sarahroodi, Somayyeh Esmaeili, Peyman Mikaili, Zahra Hemmati, and Yousof Saberi, “The effects of green Ocimum basilicum hydroalcoholic extract on retention and retrieval of memory in mice,” Ancient Science of Life, vol. 31, no. 4, Apr.-Jun. 2012, pp. 185-189, <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3644756/>.

[3] According to: Biljana Kaurinovic, Mira Popovic, and Sanja Vlaisavljevic, “In Vitro and in Vivo Effects of Laurus nobilis L. Leaf Extracts,” Molecules, vol. 15, no. 5, May 2010, pp. 3,378-3,390, <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6263372/>.

[4] For just one hint of this, see: Lokraj Subedee, R. Suresh, M. Jayanthi, H. Kalabharathi, A. Satish, and V. Pushpa, “Preventive Role of Indian Black Pepper in Animal Models of Alzheimer’s Disease,” Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research, vol. 9, no. 4, Apr. 2015, pp. FF01-FF04, <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4437082/>.

[5] Pennapa Chonpathompikunlert, Jintanaporn Wattanathorn, and Supaporn Muchimapura, “Piperine, the main alkaloid of Thai black pepper, protects against neurodegeneration and cognitive impairment in animal model of cognitive deficit like condition of Alzheimer’s disease [sic],” Food Chem. Toxicol., vol. 48, no. 3, Mar. 2010, pp. 798-802, < https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20034530/>.

[6] BrahmaNaidu Parim, Nemani Harishankar, Meriga Balaji, Sailaja Pothana, and Ramgopal Rao Sajjalaguddam, “Effects of Piper nigrum extracts: Restorative perspectives of high-fat diet-induced changes on lipid profile, body composition, and hormones in Sprague-Dawley rats,” Pharmaceutical Biology, vol. 53, no. 9, Apr. 9, 2015, pp. 1,318-1,328, <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25856709/>.

[7] Kazuya Murata, Shinichi Matsumura, Yuri Yoshioka, Yoshihiro Ueno, and Hideaki Matsuda, “Screening of β-secretase and acetylcholinesterase inhibitors from plant resources,” Journal of Natural Medicines, vol. 69, no. 1, Aug. 15, 2014, pp. 123-129, <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25119528/>.

[8] J.D.D. Tamokou, et al., “Antimicrobial Activities of African Medicinal Spices and Vegetables,” Victor Kuete, ed., Medicinal Spices and Vegetables from Africa: Therapeutic Potential against Metabolic, Inflammatory, Infectious and Systemic Diseases, London: Academic Press; Elsevier, 2017, p. 223, <https://books.google.com/books?id=SHjUDAAAQBAJ&pg=223>.

[9] Cholecalciferol, also known as Vitamin D3, is a particularly highly regarded variety.

[10] Setareh Sanati, et al., “A Review of the Effects of Capsicum annuum L. and Its Constituent, Capsaicin, in Metabolic Syndrome,” Iranian Journal of Basic Medical Sciences, vol. 21, no. 5, May 2018, pp. 439-448, <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29922422/>.

[11] “Diabetes and Alzheimer’s linked,” Mayo Clinic, May 22, 2019, <https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/type-2-diabetes/in-depth/diabetes-and-alzheimers/art-20046987>.

[12] Arguably, they’re literally identical. At least, in some preparations, they seem to be the same herb. But, since I am not experienced enough to know whether this is the usual state of affairs, I’ll stick to the more reserved word, and simply say that they’re similar.

[13] Lizzie Streit, “8 Science-Backed Benefits of Paprika,” Healthline, Aug. 20, 2019, <https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/paprika-benefits>.

[14] Hong-Gi Kim, et al., “Binding, Antioxidant and Anti-proliferative Properties of Bioactive Compounds of Sweet Paprika (Capsicum annuum L.),” Plant Foods for Human Nutrition, vol 71, no. 2, Jun. 2016, pp. 129-136, <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27184000/>.

[15] F. Márkus, H. Daood, J. Kapitány, and P. Biacs, “Change in the carotenoid and antioxidant content of spice red pepper (paprika) as a function of ripening and some technological factors,” Journal of Agricultural Food Chemistry, vol. 47, no. 1, Jan. 1999, pp. 100-107, <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10563856/>.

[16] Cinnamomum verum is sometimes designated “Ceylon Cinnamon.” It is a close cousin to the Chinese variety, Cinnamomum cassia, which is more commonly found on grocery-store shelves. According to an article in the Wall Street Journal, C. verum is considered safer than C. cassia – at least in high doses. Additionally, C. verum is assumed to share many of the same salubrious properties of C. cassia, which latter has (admittedly) been more thoroughly studied in scientific experiments. See Laura Johannes, “Little Bit of Spice for Health, but Which One? While Ceylon Cinnamon Is Milder Than Grocery-Store Variety, There Are Few Studies on Its Benefits,” Wall Street Journal, Oct. 14, 2013, <https://www.wsj.com/articles/little-bit-of-spice-for-health-but-which-one-1381786452>.

[17] Joe Leech, “10 Evidence-Based Health Benefits of Cinnamon,” Healthline, July 5, 2018, <https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/10-proven-benefits-of-cinnamon>.

[18] J. Dhuley, “Anti-Oxidant Effects of Cinnamon (Cinnamomum verum) Bark and Greater Cardamom (Amomum subulatum) Seeds in Rats Fed High-Fat Diet,” Indian Journal of Experimental Biology, vol. 37, no. 3, Mar. 1999, pp. 238-242, <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10641152/>.

[19] Just a terminological note: Coriander and cilantro are the same plant, Coriandrum sativum. Some people, in some contexts, probably use the words “coriander” and “cilantro” as synonyms. But the way I’m using these words is this. “Coriander” refers to the seeds of the plant, whereas, “cilantro” refers to the aerial parts (leaves, etc.).

[20] Helle Wangensteen, Anne Samuelsen, and Karl Malterud, “Antioxidant activity in extracts from coriander,” Food Chemistry, vol.88, no. 2, Nov. 2004, pp. 293-297, <https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0308814604001219>.

[21] B. Deepa, C. Anuradha, “Antioxidant potential of Coriandrum sativum L. seed extract,” Indian Journal of Experimental Biology, vol. 49, no. 1, Jan. 2011, pp. 30-38, <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21365993/>.

[22] For just one report on this, see: Ramit Ravona-Springer and Michal Schnaider-Beeri, “The association of diabetes and dementia and possible implications for nondiabetic populations,” Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics, vol. 11, no. 11, Nov. 2011, pp. 1,609-1,617, <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3240939/>.

[23] Yurina Mima, Nobuo Izumo, Jiun-Rong Chen, Suh-Ching Yang, Megumi Furukawa, and Yasuo Watanabe, “Effects of Coriandrum sativum Seed Extract on Aging-Induced Memory Impairment in Samp8 Mice,” Nutrients, vol. 12, no. 2, Feb. 11, 2020, pp. 455ff, <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20848667/>.

[24] Ibid.

[25] N. Thippeswamy and K. Naidu, “Antioxidant potency of cumin varieties—cumin, black cumin and bitter cumin—on antioxidant systems,” European Food Research and Technology, Jan. 12, 2005, vol. 220, pp. 472-476, <https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00217-004-1087-y>.

[26] Sushruta Koppula and Dong Kug Choi, “Cuminum cyminum extract attenuates scopolamine-induced memory loss and stress-induced urinary biochemical changes in rats: a noninvasive biochemical approach,” Pharm. Biol., vol. 49, no. 7, Jul. 2011, pp. 702-708, <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21639683/>.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Xian-Hui Li, Chun-Yan Li, Zhi-Gang Xiang, Fei Zhong, Zheng-Ying Chen, and Jiang-Ming Lu, “Allicin can reduce neuronal death and ameliorate the spatial memory impairment in Alzheimer’s disease models,” Neurosciences (Riyadh, Saudi Arabia), vol. 15, no. 4, Oct. 2010, pp. 237-243, <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20956919/>.

[29] Suresh Kumar, “Dual inhibition of acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase enzymes by allicin,” Indian Journal of Pharmacology, vol. 47, no. 4, Jul.-Aug. 2015, pp. 444-446, <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26288480/>.

[30] See: Agatonovic-Kustrin, et al., <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6334595/>, op. cit.

[31] Ana L. Colín-González, Ricardo Santana, Carlos Silva-Islas, Maria Chánez-Cárdenas, Abel Santamaría, and Perla Maldonado, “The Antioxidant Mechanisms Underlying the Aged Garlic Extract- and S-Allylcysteine-Induced Protection,” Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity, vol. 2012, 2012, p. 907,162, <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3363007/>.

[32] Biljana Petrovska and Svetlana Cekovska, “Extracts from the history and medical properties of garlic,” Pharmacognosy Review, vol. 4, no. 7, Jan.-Jun. 2010, pp. 106-110, <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3249897/>.

[33] “Health Benefits of Ginger,” WebMD, Melinda Ratini, reviewer, Nov. 6, 2020, <https://www.webmd.com/diet/ss/slideshow-health-benefits-ginger>.

[34] Nafiseh Khandouzi, Farzad Shidfar, Asadollah Rajab, Tayebeh Rahideh, Payam Hosseini, and Mohsen Mir Taherif, “The Effects of Ginger on Fasting Blood Sugar, Hemoglobin A1c, Apolipoprotein B, Apolipoprotein A-I and Malondialdehyde in Type 2 Diabetic Patients,” Iranian Journal of Pharmaceutical Research, vol. 14, no. 1, Winter 2015, pp. 131–140, <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4277626/>.

[35] Naritsara Saenghong, et al., “Zingiber officinale Improves Cognitive Function of the Middle-Aged Healthy Women,” Evid. Based Complement Alternat. Med., vol. 2012, Dec. 22, 2011, <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3253463/>.

[36] Bui Thanh Tung, Dang Kim Thu, Nguyen Thi Kim Thu, and Nguyen Thanh Hai, “Antioxidant and acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activities of ginger root (Zingiber officinale Roscoe) extract,” Journal Complementary and Integrative Medicine, vol. 14, no. 4, May 4, 2017, <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29345437/>.

[37] See: Faizul Azam, Abdualrahman Amer, Abdullah Abulifa, and Mustafa Elzwawi, “Ginger components as new leads for the design and development of novel multi-targeted anti-Alzheimer’s drugs: a computational investigation,” Drug Design, Development and Therapy, vol. 8, 2014, pp. 2,045-2,059, <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4211852/>.

[38] R. Rajamuruganab, N. Selvaganabathyc, S. Kumaraveld, C. Ramamurthyc, V. Sujathae, and C. Thirunavukkarasu, “Polyphenol contents and antioxidant activity of Brassica nigra (L.) Koch. leaf extract,” Natural Product Research, vol. 26, no. 23, Dec. 2012, pp. 2,208-2,210, <https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Dr_Chinnasamy_Thirunavukkarasu/publication/51818527_Polyphenol_contents_and_antioxidant_activity_of_Brassica_nigra_L_Koch_leaf_extract/links/55ca502608aeca747d69e63f/Polyphenol-contents-and-antioxidant-activity-of-Brassica-nigra-L-Koch-leaf-extract.pdf>.

[39] Alina Petre, “Is Mustard Good for You?” Healthline, Jan. 10, 2020, <https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/is-mustard-good-for-you>.

[40] Somayeh Kouhestani, Adele Jafari, and Parvin Babaei, “Kaempferol attenuates cognitive deficit via regulating oxidative stress and neuroinflammation in an ovariectomized rat model of sporadic dementia,” Neural. Regen. Res., vol. 13, no. 10, Oct. 2018, pp. 1,827-1,832, <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6128063/>.

[41] Jillian Kubala, “8 Science-Backed Benefits of Nutmeg,” Healthline, Jun. 12, 2019, <https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/nutmeg-benefits>.

[42] Ibid.

[43] Milad Iranshahy and Behjat Javadi, “Diet therapy for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease in view of traditional Persian medicine: A review,” Iranian Journal of Basic Medical Sciences, vol. 22, no. 10, Oct. 2019, pp. 1,102-1,117, <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6885391/>.

[44] Deborah Blum, “A Warning on Nutmeg,” New York Times, Nov. 25, 2014, <https://well.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/11/25/a-warning-on-nutmeg/>.

[45] See: Jamie Ehrenpreis, Carol DesLauriers, Patrick Lank, P. Keelan Armstrong, and Jerrold Leikin, “Nutmeg Poisonings: A Retrospective Review of 10-Years Experience from the Illinois Poison Center, 2001–2011,” J. Med. Toxicol., vol. 10, no. 2, Jun. 2014, pp. 148-151, <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4057546/>.

[46] Note: Beside the fact that “[m]yristicin is present in nutmeg” – and the related “mace” – it’s also present in “…black pepper, parsley, celery, dill, and carrots.” This is according to the chapter titled “Toxins in Food: Naturally Occurring,” by D. Hwang and T. Chen, contributors to the academic volume Encyclopedia of Food and Health (Oxford and Waltham, Mass: Academic Press; Elsevier, 2016), edited by Benjamin Caballero, Paul Finglas, and Fidel Toldrá (text excerpted at <https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/pharmacology-toxicology-and-pharmaceutical-science/myristicin>). However, I am reporting on myristicin in relation to nutmeg – and not in relation to other of the named plants – because the quantities are orders of magnitude higher in nutmeg, resulting in the fact that “…nutmeg and mace induce greater narcotic and psychotomimetic activity than” some other herbs, or even of “…an equivalent amount of myristicin or elemicin, also a component of nutmeg” separately. Ibid.

[47] Blum, loc. cit.

[48] Ehrenpreis, et al., op. cit. In fact, one report involved “…ten tablespoons of nutmeg.” Ibid.

[49] Eleesha Lockett, “Can You Get High on Nutmeg? Why This Isn’t a Good Idea,” Gerhard Whitworth, reviewer, Healthline, Aug. 31, 2018, <https://www.healthline.com/health/high-on-nutmeg>. Note that in a Google snippet, the article’s title displays as “High on Nutmeg: The Effects of Too Much and the Dangers”; whereas, on the actual Healthline website, the title reads “Can You Get High on Nutmeg? Why This Isn’t a Good Idea.” Presumably, the difference has to do with Search-Engine-Optimization (SEO) settings, which is an esoteric conversation that would implicate technical terms like “metadata” and “metatags,” and lies far afield from anything I’ll be delving into, presently.

[50] Of course, the focus of my work is on people with Alzheimer’s Disease and other forms of dementia. These conditions negatively affect memory and reasoning. Confused sufferers can sometimes expose themselves (or others) to dangers – whether advertently or inadvertently. For instance, one journal article reports on the case of one woman whose cognitively afflicted “…husband put nutmeg on his steak instead of pepper.” Els van Wijngaarden, et al., “Entangled in uncertainty: The experience of living with dementia from the perspective of family caregivers,” PLoS One (Public Library of Science), vol. 13, no. 6, Jun. 13, 2018, p. e0198034, <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5999274/>.

[51] Rachael Link, “6 Science-Based Health Benefits of Oregano,” Healthline, Oct. 27, 2017, <https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/6-oregano-benefits>.

[52] Niloufar Ansari and Fariba Khodagholi, “Natural Products as Promising Drug Candidates for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease: Molecular Mechanism Aspect,” Current Neuropharmacology, vol. 11, no. 4, Jul. 2013, pp. 414-429, <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3744904/>.

[53] Muhammad Ayaz, Abdul Sadiq, Muhammad Junaid, Farhat Ullah, Fazal Subhan, and Jawad Ahmed, “Neuroprotective and Anti-Aging Potentials of Essential Oils from Aromatic and Medicinal Plants,” Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, vol. 9, May 30, 2017, p. 168, <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5447774/>.

[54] “Researchers Call Herbs Rich Source of Healthy Antioxidants; Oregano Ranks Highest,” Science Daily, Jan. 8, 2002, <https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2002/01/020108075158.htm>; citing: American Chemical Society. On oregano outperforming other herbals in terms of its antioxidant abilities, see also: Snezana Agatonovic-Kustrin, Ella Kustrin, and David Morton, “Essential oils and functional herbs for healthy aging,” Neural Regeneration Research, vol. 14, no. 3, Mar. 2019, pp. 441-445, <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6334595/>.

[55] Aleksandar Rašković, Isidora Milanović, Nebojša Pavlović, Tatjana Ćebović, Saša Vukmirović, and Momir Mikov, “Antioxidant activity of rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) essential oil and its hepatoprotective potential,” BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicines (alternatively titled BMC Complementary Medicine and Therapies), vol. 14, Jul. 7, 2014, p. 225, <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4227022/>.

[56] As discussed in: Solomon Habtemariam, “The Therapeutic Potential of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis) Diterpenes for Alzheimer’s Disease,” Evidence Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, vol. 2016; Jan. 28, 2016, <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4749867/>.

[57] Ryan Raman, “12 Health Benefits and Uses of Sage,” Healthline, Dec. 14, 2018, <https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/sage>.

[58] Ibid.

[59] Yan-Hua Lin, Ai-Hua Liu, Hong-Li Wu, Christel Westenbroek, Qian-Liu Song, He-Ming Yu, Gert Horst, and Xue-Jun Li, “Salvianolic acid B, an antioxidant from Salvia miltiorrhiza, prevents Abeta(25-35)-induced reduction in BPRP in PC12 cells,” Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, vol. 348, no. 2, Jul. 28, 2006 [online], Sept. 22, 2006 [print], pp. 593-609, <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16890202/>.

[60] Mohsen Hamidpour, Rafie Hamidpour, Soheila Hamidpour, and Mina Shahlari, “Chemistry, Pharmacology, and Medicinal Property of Sage (Salvia) to Prevent and Cure Illnesses such as Obesity, Diabetes, Depression, Dementia, Lupus, Autism, Heart Disease, and Cancer,” Journal of Traditional and Complementary Medicine, vol. 4, no. 2, Apr.-Jun. 2014, pp. 82-88, <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4003706/>.

[61] Amanda Rose, “Antioxidants in Thyme,” Traditional Foods; The Antioxidant Project, Jun. 30, 2011, <http://www.traditional-foods.com/antioxidants/thyme/>.

[62] At least, it was the best among the five explicitly tested: bitter orange (Citrus aurantium), Fennel (Foeniculum vulgare), Mediterranean cypress (Cupressus sempervirens), Tasmanian blue gum (Eucalyptus globulus), and Thyme (Thymus vulgaris).

[63] Smail Aazza, Badiâ Lyoussi, and Maria Miguel, “Antioxidant and antiacetylcholinesterase activities of some commercial essential oils and their major compounds,” Molecules, vol. 16, no. 9, Sept. 7, 2011, pp. 7,672-7,690, <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21900869/>.

[64] Yasiel Crespo, Luis Sánchez, Yudel Quintana, Andrea Cabrera, Abdel del Sol, and Dorys Mayanchaa, “Evaluation of the synergistic effects of antioxidant activity on mixtures of the essential oil from Apium graveolens L., Thymus vulgaris L. and Coriandrum sativum L. using simplex-lattice design,” Heliyon, Jun. 15, 2019, vol. 5, no. 6, p. e01942, <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31245650/>.

[65] Soukaïna El-Guendouz, Smail Aazza, Susana Dandlen, Nessrine Majdoub, Badiaa Lyoussi, Sara Raposo, Maria Antunes, Vera Gomes, and Maria Miguel, “Antioxidant Activity of Thyme Waste Extract in O/W Emulsions,” Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland), vol. 8, no. 8, Jul. 25, 2019[online], Aug. 2019 [print], pp. 243, <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6719112/>.

[66] Masoumeh Asadbegi, Parichehreh Yaghmaei, Iraj Salehi, Alireza Komaki, Azadeh Ebrahim-Habibi, “Investigation of thymol effect on learning and memory impairment induced by intrahippocampal injection of amyloid beta peptide in high fat diet- fed rats,” Metabolic Brain Disorder, vol. 32, no. 3, Mar. 2, 2017 [online], Jun. 2017, [print], pp. 827-839, <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28255862/>.

[67] Monika Sienkiewicz, Monika Łysakowska, Paweł Denys, and Edward Kowalczyk, “The antimicrobial activity of thyme essential oil against multidrug resistant clinical bacterial strains,” Microbial Drug Resistance, vol. 18, no. 2, Nov. 21, 2011 [online], Apr. 2012 [print], pp. 137-148, <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22103288/>.

[68] Julie Jurenka, “Anti-inflammatory properties of curcumin, a major constituent of Curcuma longa: a review of preclinical and clinical research,” Alternative Medicine Review, vol. 14, no. 2, Jun. 2009, pp. 141-153, <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19594223/>.

[69] “The health benefits of turmeric,” Nuffield Health, Nov. 18, 2020, <https://www.nuffieldhealth.com/article/the-health-benefits-of-turmeric>.

[70] Terry Naturally, “The ways turmeric and curcumin differ might surprise you,” USA Today, May 1, 2019, <https://www.usatoday.com/story/sponsor-story/terry-naturally/2019/05/01/ways-turmeric-and-curcumin-differ-might-surprise-you/3541923002/>.

[71] Ibid.

[72] Susan Hewlings and Douglas Kalman, “Curcumin: A Review of Its’ Effects on Human Health,” Foods, vol. 6, no. 10, Oct. 22, 2017, p. 92, <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5664031/>. A similar extract is sometimes referred to as “bioperine.”

[73] Kayoko Miura, Hiroe Kikuzaki, and Nobuji Nakatani, “Antioxidant activity of chemical components from sage (Salvia officinalis L.) and thyme (Thymus vulgaris L.) measured by the oil stability index method,” J. Agric. Food Chem., vol. 50, no. 7, Mar. 27, 2002, pp. 1,845-1851, <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11902922/>.

[74] Though, see my YouTube-video presentation Antioxidants, Part 2 to discover gamma-tocopherol, a form of Vitamin E more commonly found in seeds – such as sesame seeds, which are on my list.

[75] M. Saljoughian, “Natural Powerful Antioxidants,” U.S. Pharmacist, vol. 1, Jan. 23, 2007, p. HS38-HS42, <https://www.uspharmacist.com/article/natural-powerful-antioxidants>.

[76] Caroline Hill, Jun. 5, 2018, <https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/vitamin-c-foods>.

[77] Also, pasteurization or processing can cause the vitamin content (especially in the case of Vitamin C) to diminish.

[78] Alexander Yashin, Yakov Yashin, Xiaoyan Xia, and Boris Nemzer, Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland), vol. 6, no. 3, Sept. 15, 2017, p. 70, <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5618098/>. Innumerable other articles could be given at this point, including many cited elsewhere in this post, or in any of the companion videos, but also: T. Alan Jiang, “Health Benefits of Culinary Herbs and Spices,” Journal of AOAC International, vol. 102, no. 2, Jan. 16, 2019 [online], Mar. 1, 2019 [print], pp. 395-411, <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30651162/>.